The genius of Albrecht Durer

A painter's icon throughout the ages

Albrecht Durer was the first German artist to emerge north of the Alps

who achieved a highly developed artistic self-awareness based on the model

of the Italian Renaissance, as well as a high degree of acceptance in

society. Being German, he continued throughout his life to receive

important artistic stimuli from the Netherlands and Italy. While Durer was

more strongly influenced by Flemish art during his early period, possibly

a result of the Franconian workshop tradition of his master Michael

Wolgemut, in the period after his journeys to Italy he

mainly worked with ideas from the Italian Renaissance which enabled him to

create new images.

Albrecht Durer was the first German artist to emerge north of the Alps

who achieved a highly developed artistic self-awareness based on the model

of the Italian Renaissance, as well as a high degree of acceptance in

society. Being German, he continued throughout his life to receive

important artistic stimuli from the Netherlands and Italy. While Durer was

more strongly influenced by Flemish art during his early period, possibly

a result of the Franconian workshop tradition of his master Michael

Wolgemut, in the period after his journeys to Italy he

mainly worked with ideas from the Italian Renaissance which enabled him to

create new images.

Durer's varied interest in nature and the environment, his study of the works of other masters, and his inspired ability to transform this innovatively, contributed to the important stimulus he gave to the historical development of art, starting north of the Alps, but eventually extending throughout Europe. For example, he was the first artist north of the Alps to paint a self-portrait, and his watercolors were the first autonomous landscape depictions that were freed from the context of Christian iconography.

He was able to take part as an equal in discussions held in circles of famous academics and humanists, and acquired humanist knowledge himself. Studies of the classical period, interpreted by the Italian Renaissance artists, left their mark on his work.

Durer was perfectly adept at brilliantly applying the discovery of central perspective, Vitruvius' (born c. 84 B.C.) canon of human proportions and Da Vinci's (1452 - 1519) theory of the ideal proportions of the horse, to his own art and in particular to his prints. During his lifetime he had already ensured his lasting fame by, for example, having his prints sold abroad by commission agents. This process of choosing new methods of distribution as an independent entrepreneur was an example of the new self-awareness of an artist who gradually distanced himself from his Late Medieval status as a craftsman dependent on commission work.

After his death, Durer remained one of the most highly regarded of artists for centuries. Even today, the term "Durerzeit" (age of Durer) represents the process of transition from the late Middle Ages to the Renaissance in Germany.

The quality and wide range of his works and themes, both in terms of content and formal aspects, are also astonishing. Durer's woodcuts and copper engravings made him famous throughout Europe; today he is still regarded as the greatest master of his age in the field of printed graphics. On account of his abilities as a graphic artist and painter, his contemporaries called him a second Apelles, after one of the most famous classical painters who lived during the fourth century B.C. Though his paintings were normally produced as the result of a commission - his two main areas of focus were portrait painting and the creation of altar pieces and devotional pictures - Durer enriched them with unusual pictorial solutions and adapted them to new functions.

His watercolors and drawings are impressive due to their thematic and technical diversity. They demonstrate both Durer's careful method of working when preparing his paintings and his special interest in the surrounding nature.

Fortunately, and in contrast to other artists, many of his works still exist, enabling a comprehensive picture of his work to be created. In addition to 350 woodcuts and copper engravings, 60 paintings and about a thousand drawings and watercolors are known to exist.

During the course of the years Durer achieved the status of icon, and examples of this recognition include the reception of his Self-portrait in a Fur-Collared Robe and the way admiration of him was expressed in the 19th century by the erecting of monuments.

While from the 16th to the 19th centuries it was mainly artists and

collectors who promoted the adoption and admiration of Durer and his

works, an academic reappraisal of his work, which was able to base itself

on extensive source materials, began in the 19th century. Durer's written

legacy includes autobiographical writings, theoretical treatises and diary

entries as well as poems and letters to clients and humanists who were

among his friends. Durer is the first German artist from whom such an

extensive selection of private remarks and letters have survived,

permitting us to draw conclusions about the artist as a person.

Contemporaries such as the Nuremberg patrician Christoph Scheurl (1481 -

1542) provide further clues, as do famous artistic biographers such as the

Dutch Karel van Mander (1548-1606), the German artist Joachim von Sandrart

(1606 - 1688) and the artist, architect and architectural theoretician

Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574). This extensive heritage does not merely,

however, make it possible to gain a clearer picture of the character and

figure of Durer than is possible for other artists of his age; his written

legacy enabled Durer to take up a unique position in his age, in which he

also differs from his predecessors and successors.

While from the 16th to the 19th centuries it was mainly artists and

collectors who promoted the adoption and admiration of Durer and his

works, an academic reappraisal of his work, which was able to base itself

on extensive source materials, began in the 19th century. Durer's written

legacy includes autobiographical writings, theoretical treatises and diary

entries as well as poems and letters to clients and humanists who were

among his friends. Durer is the first German artist from whom such an

extensive selection of private remarks and letters have survived,

permitting us to draw conclusions about the artist as a person.

Contemporaries such as the Nuremberg patrician Christoph Scheurl (1481 -

1542) provide further clues, as do famous artistic biographers such as the

Dutch Karel van Mander (1548-1606), the German artist Joachim von Sandrart

(1606 - 1688) and the artist, architect and architectural theoretician

Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574). This extensive heritage does not merely,

however, make it possible to gain a clearer picture of the character and

figure of Durer than is possible for other artists of his age; his written

legacy enabled Durer to take up a unique position in his age, in which he

also differs from his predecessors and successors.

Durer's theoretical treatises give us concrete information regarding his methods of working, his didactic abilities and the theoretical and scientific knowledge which enabled him to write them. A good example of this is Durer's treatise on painting, called Speis der maier knaben (Nourishment for Young Painters), in which he explains the tasks and opportunities of painting and their application to his students. During recent decades, research on Durer has progressed with a flood of contributions. Matthias Mende's bibliography, which appeared on the occasion of the 500th anniversary of Durer's birth, contains more than ten thousand bibliographical references.

Every Durer revival since the 16th century has brought with it new views and insights. There ate countless statements from artists, collectors and observers. The academic examination of the figure of Albrecht Durer and his works has continued, with unbroken interest, right up to the present. Although numerous research contributions appear every year on this theme, the complexity of his works means that researchers are constantly faced with new questions. Even in the future, Durer will remain a phenomenon deserving of continuing attention.

From goldsmith to painter

Albrecht Durer's immediate ancestors lived in Hungary. His origins are

confirmed by the occasionally patchy family chronicle, much cited in

academic works, that Albrecht Durer wrote later in life, on 25 December

1523, based on records kept by his father. Albrecht Durer the Elder

(1427-1502) came from a small Hungarian village called "Eytas" close to "a

small town called Jula." The place being described is now known as Ajt,

Durer wrote later in life, on 25 December 1523, based on records kept by

his father. Even today it has not been shown beyond doubt whether the

Durers came from Hungary or Germany. It is possible that at least a part

of the family was of German origin, as Albrecht Durer the Elder's written

German was excellent, and his son also occasionally disassociated himself

from other nationalities using the term "Albertus Durerus Germamcus." The

family name is a translation of the Hungarian "ajtos," "Tur" (door) in

German, and appears in writing as "Thurer" or "Turer." The coat of arms on

the back side of Durer's earliest portrait of his father shows a gateway

with open doors, possibly a barn door as an allusion to his ancestors'

trade, for they were cattle breeders.

Albrecht Durer's immediate ancestors lived in Hungary. His origins are

confirmed by the occasionally patchy family chronicle, much cited in

academic works, that Albrecht Durer wrote later in life, on 25 December

1523, based on records kept by his father. Albrecht Durer the Elder

(1427-1502) came from a small Hungarian village called "Eytas" close to "a

small town called Jula." The place being described is now known as Ajt,

Durer wrote later in life, on 25 December 1523, based on records kept by

his father. Even today it has not been shown beyond doubt whether the

Durers came from Hungary or Germany. It is possible that at least a part

of the family was of German origin, as Albrecht Durer the Elder's written

German was excellent, and his son also occasionally disassociated himself

from other nationalities using the term "Albertus Durerus Germamcus." The

family name is a translation of the Hungarian "ajtos," "Tur" (door) in

German, and appears in writing as "Thurer" or "Turer." The coat of arms on

the back side of Durer's earliest portrait of his father shows a gateway

with open doors, possibly a barn door as an allusion to his ancestors'

trade, for they were cattle breeders.

His grandfather Anton Durer had learned the craft of the goldsmith, and his eldest son, Durer's father, was supposed to follow in his footsteps. The latter, however, left his homeland at an early age and went off on his travels. The imminent danger of a Turkish invasion and the Hussite Wars in Bohemia were reason enough to turn his back on Hungary. Albrecht Durer the Elder spent a short while in Nuremberg around 8 May 1444, but did not return to the Franconian city until 1455 in order to work as an assistant in the workshop of the Nuremberg goldsmith Hieronymus Holper (died 1476) after, so it was said, he had been "a long time in the Netherlands with the great artists."

In 1467, after working as an assistant for twelve years, he married Barbara Holper (1451-1514), the 15 year-old daughter of his master. Marrying a citizen of Nuremberg enabled him to gain civil rights in the city and in 1468, at the advanced age of 41, he qualified as a master. At first the newly married couple lived at the rear of the home of Dr. Johannes Pirckhamer (died 1501), a Nuremberg patrician. This is where

Albrecht Durer the Younger was born on 21 May 1471, their third child. Of his eighteen brothers and sisters, only three brothers survived apart from him: Hans the Elder (born 1478), Hans the Younger (1490-1534/35 or 1538) and Endres (1484-1555). Durer spent his childhood and youth in the smart Latin quarter of Nuremberg. The family lived in the house "unter den Vesten" "which Durer's father had bought in 1475 for 200 florins.

Both of Durer's grandfathers, and his father, were goldsmiths. It was intended that he should continue this tradition. After he had "learned to write and read" in school, his father started him as an apprentice in his workshop. He was a bright student, but soon showed greater interest in painting than in the goldsmith's craft, so that according to his family chronicle his father regretted "the lost time" that his son "had spent learning gold work." This is the period from which Durer's first work dates, a drawing in silver point which demonstrates his inherent ability to draw. At the age of 13, before a mirror, he drew the earliest remaining of the numerous self-portraits that were to record his appearance at various points in his life. Durer noted in the inscription: "Daz hab jch aws eim spiegell nach mir selbs kunterfet im 1484 jar, do ich noch ein kint was" ("I drew this myself using a mirror in the year of 1484, when I was still a child"). The silver point drawing depicts the artist's characteristic, childlike features in a style that is still Late Gothic and somewhat angular, but already demonstrates an assured hand. The young Durer coped with playful ease with the difficult silver point technique, which cannot be corrected and requires a high degree of precision and stylistic confidence. It is the only existing autonomous self-portrait of an artist at such an early age. According to a source, an even earlier self-portrait of Durer at the age of eight was owned by the Bavarian Elector. It was destroyed in the course of a palace fire.

It is probable that the father recognized his son's talent, for in 1486 he finally gave in to his wishes and sent him to become an apprentice in the workshop of the respected Nuremberg painter and entrepreneur, Michael Wolgemut. Christoph Scheurl, a humanist and personal friend of Durer's, reported that the artist had informed him both verbally and in writing that his father wanted to apprentice him at the early age of fifteen to the famous, internationally renowned graphic artist Martin Schongauer (c. 1450-1491).

Schongauer, who was also the son of a goldsmith, produced copper engravings in larger editions than had previously been customary. This increased the familiarity of his works, which were soon so popular that they were also used by other artists of the late 15th century as models for their altars and panel paintings. During this time, selected masterly engravings by Schongauer could be found in many workshops and had a stylistic influence. In his Lives of the Artists, the artist and biographer Giorgio Vasari reports that even Michelangelo (1475-1564) had copied a copper engraving by Schongauer.

The question as to why Durer's father finally decided in favor of Wolgemut as a master must remain open. It is possible that the Durer family could not afford the expensive journey and living and apprenticeship costs. Perhaps the famous Schongauer also no longer wanted to take on any more apprentices.

It seems reasonable to assume that Durer had already finished his apprenticeship as goldsmith with his father at this time. The knowledge of drawing which he had gained doing this was to prove useful later on when making precise preparations for paintings in the form of underpaintings and preliminary drawings. The years spent as an apprentice with Michael Wolgemut, whose style was still rooted in the Late Medieval craftsmen's tradition, were extremely useful for Durer's artistic development, though they do not always appear to have been entirely easy from a human point of view. For example, at the age of 15 Durer was the oldest apptentice in the workshop and had to "suffer much from (Wolgemut's) servants," as he himself wrote in his family chronicle.

In his master's workshop, Durer learned the fundamental things necessary for his training as a painter's assistant. In addition to the basic requirements such as mixing colors, composition, pen and ink drawings and producing landscape backgrounds, there was also the intensive study and use of the technique of woodcuts. This is all the more remarkable as at that time Michael Wolgemut worked with the well-known publisher Anton Koberger (c. 1440/45-1513), who was Durer's godfather, and employed wood block carvers to cut the preliminary drawings into the wood engraving block.

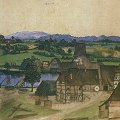

Woodcut illustrations from Michael Wolgemut's workshop were at the time some of the best in terms of technique that were available on the European market. New effects in their preparation, finer interior details and the suggestion of spatiality increased demand. The 645 illustrations for the Nuremberg Chronicle by the Nuremberg doctor and humanist Hartmann Schedel (1440-1514), which was published by Anton Koberger, became particularly famous. This work, which appeared in 1493, contained a total of 1809 woodcuts and, with its illustrations and descriptions based on the seven ages, was meant to represent a history of the world and its peoples. The chronicle became internationally famous, and the 123 pictures of cities may have contributed considerably to its popularity. The largest depiction, a view of the then world and trade metropolis of Nuremberg, is a good example of the way city views were recorded in all their detail.

Repeated attempts have been made to stylistically prove Durer's involvement in this book project by comparing it to his woodcuts of the Apocalypse. While there is no source material to confirm his collaboration, it can be assumed that he did so, as Durer was working as an apprentice in Wolgemut's workshop at the time the Nuremberg Chronicle was produced.

The intensive study of woodcut techniques and what were, for the time, exceptionally high technical standards in the Wolgemut workshop were important prerequisites for Durer's inspired potential for development in this field, and for his methodical action in later years when he started to use printed graphics to a broadly commercial extent.

In 1490, after his painter's apprenticeship in Michael Wolgemut's workshop ended, Durer left on four years of travels as a journeyman, and immediately before departing painted the two portraits of his parents which were originally connected in the manner of a diprych and were separated after 1588. While the portrait of his father came to be owned by Emperor Rudolph II in Prague, its counterpart remained with the Imhoff family in Nuremberg.

These first painted portraits by Durer demonstrate the knowledge and abilities he had gained in the Wolgemut workshop.

The subjects appear before a dark background and are related to each other by their lines of sight. Their piety is expressed by the rosaries in their hands. The delicate detail of the features, in particular those of the father, is realistic to a degree which is unusual in contemporary portrait painting, and is reminiscent of Dutch portraits of the early 15th century. In the arrangement and opposite positions of the pendants, Durer was following the traditional scheme of portraits of married couples. The woman is positioned to the right of the man, the lower ranking position. The folds of the garments, particularly in the mother's portrait, still show a Late Gothic hardness. Uncertainties in the modeling of the features suggest that the portraits must have been created immediately after Durer's apprenticeship had ended.

The goal of an emerging artist when making a journey was to get to know other workshops, methods of work and styles, and to extend his own repertoire in terms of techniques and motifs. Artistically interesting motifs were recorded in sketch books which were used after the artist returned from his journey to help him find his own forms. Such sketches made by Durer, taken out of a sketch book, still exist.

In his family chronicle, Durer refers to his time as a journeyman with just one laconic sentence: "And as I had finished my apprenticeship, my father sent me away, and I stayed away for four years, until my father called for me again. And I left in 1490, after Easter, and returned again, in the year of 1494, after Whitsun."

Nothing is known about the places Durer stayed at during the first two years of his journey, although portrait drawings such as the Self-portrait with a Bandage presumably date from this time. The theory that Durer possibly stayed in Haarlem in the Netherlands during this time cannot be proven, although it was suggested by the art historiographer and artist Karel van Mander in his lives of the artists Het Schilder-Boeck, which first appeared in 1604, by Joachim van Sandrart in his book Teutschen Academie der Edlen Bau-, Bild- und Mahlerey-Kunste, and was assumed to be the case due to references to paintings by the Haarlem master Geertgen tot Sint Jans (c. 1460 - 1490). It is also called into question by a statement by the Nuremberg humanist Christoph Scheurl, a personal friend of Durer's. In his work, Vita reverendi patris domini Antoni Kressen Nurnberg, dating from 24 July 1515 it says: "Then, after he had traveled back and forth in Germany, he came to Colmar in 1492...".

Encounter with proportion and perspective

The first Italian journey

At the end of May 1494 Durer returned to Nuremberg where he married

shortly afterwards on 7 July. The family chronicle provides the following

information about this:

At the end of May 1494 Durer returned to Nuremberg where he married

shortly afterwards on 7 July. The family chronicle provides the following

information about this:

"And when I arrived home once more, Hans Frej negotiated with my father and gave me his daughter called Agnes with 200 florins and held the wedding. This was on the Monday before St. Margaret's in the year of 1494."

It was an arranged marriage, a "good catch" which Durer's father had initiated for economic reasons. Hans Frey (1450-1532), Durer's father-in-law, was a master craftsman, a smith from an old Nuremberg family who had specialized in air-driven fountains, machines and banqueting tables, was the site manager and landlord of the town hall, and was elected to the city council in 1496. His wife Anna, nee Rummel (died in 1521), also came from a wealthy and respected family. One of her relatives was the wealthy financier Wilhelm Rummel, who worked mainly in Italy for the Emperor, the Curia and the Medicis.

At the time of her marriage to Durer, Agnes Frey was about 18 or 19 years old. A pen drawing in the Albertina collection, bearing the caption "mein agnes" added by Durer himself, shows her as she might appear when nobody was looking, as a childlike girl with her hair tied back. It is possible that this sketch was even produced before they were married, as Agnes appears without a bonnet, in accordance with the custom for unmarried women.

It can be clearly recognized from various letters from Durer to Willibald Pirckheimer dating from the second Italian journey in 1506 that Durer's marriage, which did not produce any children, was an unhappy one. This is confirmed in later years by the meticulous records in the Netherlands journal, from which it emerges that during the course of the one year trip, Durer took most of his meals together with his numerous friends or alone, while his wife and maid were able "to cook and eat upstairs." Despite this he depicted his wife, who despite all personal differences was a competent business partner and traveled to the fairs and markets with his printed graphics, in numerous portraits. In later years she was his model in the painting of St. Anne. It has been speculated at various times that Durer was homosexual, based on a letter by the Nuremberg patrician Lorenz Behaim (died 1518) to Willibald Pirckheimer on 7 March 1507, in which "Durer's boys" are spoken of. There is, however, no further evidence of this.

A few months after the wedding Durer left on his first Italian journey. The only evidence of this trip is a mention in a letter wrirten during his second period in Italy in 1506/07, in which Durer tells Willibald Pirckheimer: 'And the thing that I liked so much 11 years ago no longer pleases me now."

What is meant here is either a work of art that cannot be more closely identified, or the Italian style in general which may have made a deep impression on Durer as a young journeyman on his first trip to Italy. By the time of his second Italian journey, however, he had already developed his own style and artistic ideas, for which reason he may have remained calm in the face of external influences.

The reason for Durer's sudden departure for Italy in 1494 has frequently been thought to have been the outbreak of the Plague in Nuremberg, which during its worst phase killed over a hundred people every day. As early as 1483, in a report requested by the city council, the Nuremberg city doctors - in imitation of the Florentine doctor and philosopher Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499) - recommended that the most effective preventative measure against the plague was fleeing from the city. Respected Nuremberg citizens such as the artist Christoph Amberger (c. 1500-1561/62) and Durer's godparent Anton Koberger withdrew to the country to escape the risk of infection.

The plague raging in Nuremberg was probably not the only reason Durer left on so long a journey. This was frequently viewed as a sort of extended journeyman's travels. This later became decisive in Durer's role as a mediator between the Italian Renaissance and Germany, breaking through his customary way of depicting things, marked by the Late Medieval workshop tradition, to reveal the "new" element in Italian art, the recollection of the classical world.

A decisive element in Durer's interest in making this journey to Italy may have been the desire to learn from the sculptural and spatial conceptions of classical art and the Italian Renaissance artists and to understand the practice and theory of what the latter were striving for, the overlapping of the "image of man, perspective, proportion, the classical age, nature, mythology and philosophy." In this area, German art had remained stuck at a Late Medieval level.

Durer probably first heard of the new trends in Italian art while he was in Basle. The first examples to reach the North were graphic sheets and devotional pictures. Drawn copies of a series of copper engravings by a master from Ferrara from about 1470 are some of the earliest proofs of northern interest in Italian Renaissance art. Copper engravings made by the Italian artist Andrea Mantegna (1431-1506) were in circulation in Germany even before Durer's Italian journey. Durer traced them directly from the original sheets, though it is uncertain whether he did this immediately before his journey or during his stay in Italy.

Durer's first Italian journey is an important milestone in his artistic development. First of all, he was no longer familiar with southern art merely in the form of printed graphics, as was the case north of the Alps, but was able to see the works on the spot.

Basing their insights on the classical architectural theoretician Vitruvius, Italians were studying both the ideal proportions of the human body and the development of central perspective as a means to a more realistic depiction of space. Durer was to learn about all these things from Italian artists such as Jacopo de Barbari (c. 1440/1450-1515) and Giovanni (1430-1516) and Gentile Bellini (1429-1507), with whom he may have become acquainted in Venice at the arrangement of Nuremberg merchants. There is, however, no evidence as to whether he ever sketched directly from antiques or whether he received his knowledge of classical forms solely from copying engravings made by Italian masters.

The route of Durer's journey presumably first took him via Augsburg to Innsbruck, where he drew the two watercolors of the courtyard of Innsbruck Castle. These are the first two in a series of landscape watercolors which were created during the journey. They were used as independent study material and private records. Later they were also incorporated into Durer's printed graphics and the landscape backgrounds of his paintings. There are a total of 32 water-colors dating from the period between 1494 and shortly after 1500, most of which are connected with

Durer's travels to Italy. None of the sheets is signed or dated. For this reason there is to date no agreement concerning their precise sequence. The watercolors are some of the most studied in Western art history. They can rightly be considered autonomous works and document an altered relationship with landscape painting, which had previously been the least regarded artistic genre, its function being entirely subservient to history paintings. A decisive factor in the new conception of landscape pictures is an individual concept of nature as well as an innovative technique in using watercolors, making it possible to produce the subtlest nuances by building up layers of glaze similar to the technique used in oil painting. While Durer's early watercolors are still reminiscent of typical examples of topographical methods of depiction from the Franconian workshop tradition, such as the views of Bamberg from the workshop of Wolfgang Katzheimer (active from 1478-1508), in the later works their composition, color and painterly design becomes considerably more free. The atmospheric conception of landscape in these later watercolors has even led to their being compared to those of the impressionist, Cezanne (1839-1906).

Durer's watercolors can be divided into two groups. The early examples frequently include topographical studies which are the first autonomous colored landscapes to record particular locations in detail. They still contain some perspectival uncertainties, such as the depiction of the Wire-drawing Mill. Here, the artistic interest in producing a realistic picture is at the fore. This leads to all details being recorded additively with the same emphasis, and the color being softened very little. His knowledge about the influence of light and air on the appearance of color only becomes noticeable in later works. These move from a natural to an atmospheric and cosmic record of landscape, which becomes clear both in the overall composition and in the more relaxed use of color. The detailed record is now subordinate to the harmonious effect of the whole. A single motif that aroused Durer's interest, such as a section of wall, a mass of roots in a quarry or a complex of buildings, may stand out from the otherwise summary picture, captured with a few brushstrokes and color surfaces. In later, mature watercolors such as the Quarry dating from about 1506, a section is placed freely on the surface of the picture. Here, Durer is experimenting with the technical opportunities of watercolor by allowing various brown tones to come into effect in numerous nuances and shades. The knowledge of perspective gained in Italy was already leaving its mark on watercolors such as the Landscape near Segonzano in the Cembra Valley, making them easier to date.

His road led on across the Brenner Pass and through the Eisack Valley to Venice. The likely route can partly be deduced from the watercolors, and partly from information about frequently used routes that has been handed down in the first map printed as a woodcut, complete with travel routes and distances, by the mathematician and doctor Erhard Etzlaub (c. 1460-1532). According to this, Albrecht Durer's route would have taken him from Innsbruck on the road over the Brenner Pass, then to Bressanone (Brixen) and Chiusa (Klausen), where a watercolor of the Rabenstein near Weidbruck was created. According to the "Bolzano Chronicle" dating from 1494, the roads near Bolzano (Bozen) were flooded at the time of Durer's journey. It is therefore likely that the artist made a detour through the Cembra Valley, which is confirmed by the watercolor. During his return trip, on the road to the Brenner, he probably created a view of Klausen in the Eisack Valley which has since been lost, though it was reworked in the copper engraving Nemesis or Good Fortune.

Durer's stay in Venice, however, was characterized mainly by drawings produced from originals and from life. Throughout his life, Durer expressed his enthusiasm for the variety of fauna and flora in numerous drawn studies. During his stay in Venice, the large-format water study sheets with depictions of a Sea Crab and a Lobster were created. Initially there was doubt about the authenticity of these sheets, but Winkler established that the lobster was a member of a species predominantly native to the Adriatic Sea. Studies of lions, reminiscent of Venice's heraldic animal, and mythological depictions have also survived. These sheets, like the watercolors, were independent studies not made in preparation for any concrete work.

In Venice, Durer copied from works by Mantegna, Lorenzo di Credi (1456/1460-1537) and Antonio del Pollaiuolo (1430 - 1498), and here his interest in nudes was in the foreground. Studies such as the Female Nude of 1493 provide evidence that Durer had already considered the depiction of human proportions before his journey to Italy. A prominent example of drawn copies of Italian originals is the pen drawing of the Death of Orpheus in the Hamburg Kunsthalle, which Durer probably produced in imitation of a painting by Mantegna. The original is only known by a copper engraving which is also in the Kunsthalle in Hamburg. The pictorial theme was drawn from the eleventh chapter of Ovid's Metamorphoses (1-43): the classical hero and famous singer Orpheus is killed by two women during a feast of Bacchus in Thrace for having introduced homosexual love to Thrace. This early drawing already demonstrates something that was to become significant in Durer's later graphic works: recording the human body in motion had priority over narrating the mythological theme. The sweeping gestures of the two Thracian women, both seen from the front and the back, form a counterweight to the movement of Orpheus' body. The study of human proportions and search for the ideal measurement were echoed in numerous other nudes such as the standing nude woman seen from the rear.

On repeated occasions, Durer spontaneously recorded new impressions from life. This is also documented by the studies of Venetian women wearing the city dresses with very low necklines that were widely considered to be "indecent". In a pen drawing Durer contrasts a Venetian with a Nuremberg woman, and the liberal Venetian dress clearly differs from the tight and modestly laced German costume.

In this connection, Erwin Panofsky compares Durer with a modern art historian contrasting a Late Gothic town house and a Renaissance palazzo in a similar manner. Studies of traditional Venetian dress reappear in Durer's printed works at a later date, such as in the drawing and woodcut of the Martyrdom of St. Catherine and the depiction of the Babylonian Whore in the series of woodcuts for the book of the Apocalypse.

It has frequently been questioned how Durer managed to finance this journey to Italy. It is possible that he was able to invest a portion of his wife's dowry, but it is likely that he kept his head above water by selling woodcuts, perhaps even by doing commissioned work. Researchers differ in their opinions about Durer's activities as a painter during his first journey to Italy, as there is no corresponding painting that can be definitely attributed to this period by means of a signature or sources.

The picture of the Virgin and Child that is now in a private collection but used to be in the Capuchin monastery of Bagnacavallo near Bologna is considered by Anzelewsky to be part of a group of four paintings which were possibly created during the first journey to Italy. There are other opinions, to the effect that Durer possibly painted the picture after his return to Nuremberg and took it with him on his second Italian journey in order to sell it there. The work was not tediscovered until after the Second World War. Before this time it had been in Italy.

In this picture, the Late Gothic style is already combined with the first hints of the Italian Renaissance. The Virgin is enthroned before a gate arch which opens to one side, the Christ Child bedded on a cloth on her lap. In terms of composition, the group of figures is in the shape of a triangle. Mary and Jesus are related to each other by their postures. The mother is tenderly holding her son's hand and gazing at him both lovingly and mournfully, foreseeing his Passion to come. The strawberry twig in Mary's hand, a symbol of both Christ and Mary, is a sign both of motherhood and, because of its red color, of Christ's Passion. In the monumental and well-proportioned conception of the group of figures Durer was following Italian models, in particular the Madonna paintings by Giovanni Bellini, though the spatial composition still owes much to the Late Gothic style as influenced by Dutch painting. The physiognomy of the Christ Child is reminiscent of Durer's drawing of a reclining Christ Child after Lorenzo di Credi. While this drawing is not a concrete model, there are nonetheless stylistic parallels.

During the following decades, the achievements of Italian Renaissance art, as conveyed by both printed graphics and the works and writings of Durer, enabled all genres of art north of the Alps to take a decisive step forwards. Artists no longer went just to the Netherlands in order to study the originals of great masterpieces by painters such as Jan van Eyck (c. 1390-1441) or Rogier van der Weyden (1399/1400- 1482), copy them and continue work on them after they returned home; now they also allowed Italian forms to leave their stylistic mark on their works. Many German artists, however, merely fed on the indirect influence of printed graphics and did not journey to Italy themselves.

A revolution in printed graphics and painting

"But Durer, however admirable in other respects - what cannot he

express in monochrome, that is with black lines? Light, shade, splendor,

the sublime, depths; and, although it has started from the position of a

single object, the eye of the observer is offered much more than an

aspect..." (Erasmus of Rotterdam, in de recta Latini Graecique sermonis

pronuntiatione, 1528)

"But Durer, however admirable in other respects - what cannot he

express in monochrome, that is with black lines? Light, shade, splendor,

the sublime, depths; and, although it has started from the position of a

single object, the eye of the observer is offered much more than an

aspect..." (Erasmus of Rotterdam, in de recta Latini Graecique sermonis

pronuntiatione, 1528)

In 1495 Durer returned to Nuremberg and started by putting the knowledge and ideas he had gained during his five year journey into practice in printed graphics, though a few years later he also applied them to paintings. The time after his journey can be termed the first high point in Durer's creative work, during which, in a very short period, he perfected his abilities and revolutionized printed graphics and painting in terms of function, methods of depiction, themes and technical methods in a way no other artist of his age did. Between 1495 and 1500 about a dozen paintings and over sixty printed sheets were produced. The latter also comprise, in addition to almost the entire series of the Great Passion and the Apocalypse, seven large format single-leaf woodcuts and 25 engravings which he printed on his own printing press in the Nuremberg workshop he founded in 1495, and upon which his international fame was to be based.

In addition, Durer was the first German artist to find new opportunities for production and distribution. Technical reproducibility, the possibility of reusing worked wood engraving blocks and copper plates as setting copies and printing high print runs, was something he used to a degree previously unknown. He was the first to introduce the production of printed graphics in his own publishing business on an equal footing with the running of a painter's workshop.

In contrast to his teacher Michael Wolgemut, Durer produced his printed graphics in advance and not on commission. This meant that in this medium he was independent of the traditional iconography and of the prescriptions normally stipulated by paying customers when ordering works. At that time, the artist was still considered to be a craftsman, an agent who had to meet the client's requirements. Durer's new method of using the medium of printed graphics made a considerable contribution towards changing artists' self-image in Germany and raising their social acceptability. In this way the artist emancipated himself from being a simple craftsman to being the more self-determined "creator" of new themes or new artistic interpretations of existing themes. A sign of this increasing self-determination, independent of the traditional social understanding of artists, is the process of signing and dating printed graphics. The fact that Durer's copyright was shamefully ignored suggests that the signature was an attempt to guard against abuse. Letters which Durer wrote to Jakob Heller (c. 1460 - 1522) in 1507 clarify his endeavor to apply his ideas and knowledge independently of clients. This is probably also the reason why the emphasis of his work during the first five years after the foundation of his workshop was on the area of printed graphics. During this time he perfected his engraving technique and achieved his own style which has yet to be surpassed technically. Durer also applied the experience he gained in this way to woodcuts, which he liberated from their Late Gothic stylistic forms. He enabled both techniques, which he treated equally in his work, to achieve new pioneering forms of expression.

In addition to the artistic, it was probably also the commercial possibilities of the new medium that proved decisive. As early as 1497 Durer engaged his first art dealer, Conrad Swytzer, who was to offer the prints for sale at the highest possible prices - as established in the contract - by taking them "from one place to the next and from one town to the next." Nuremberg was the ideal place to produce and sell printed graphics. On the one hand, the city had been a center of parchment, and later of paper production since the Middle Ages, and on the other hand copper crafts were also widespread there, so that the workshops' demand for copper engraving plates could be met without difficulty. The numerous Nuremberg city festivities, fairs with shooting matches, funfairs and annual "Heiltumsfest" provided an outstanding sales opportunity.

Durer's earliest monogrammed copper engravings date from the time immediately after his first Italian journey, and they are still influenced by Martin Schongauer, particularly as regards their figural composition. There are about 30 engravings dating from this period. They are not dated at this point, something that Durer started adding to his sheets from 1503 onwards.

The course of Durer's artistic development in this technique can be followed in a sequence consisting of about 13 engravings. One can detect a gradual refinement of his use of lines which become continually more painterly and free.

Years of theoretical and artistic research

The turn of the century marked a fundamental change in Durer's style

and view of the world. He studied the artistic theories of the Renaissance

more intensively than ever, in particular the theory of the ideal

proportions of the human body and central perspective. His interest in

these themes is documented in numerous works. Printed graphics also

provided him with undreamed of opportunities for experimentation free of

the prescriptions relating to commissioned works.

The turn of the century marked a fundamental change in Durer's style

and view of the world. He studied the artistic theories of the Renaissance

more intensively than ever, in particular the theory of the ideal

proportions of the human body and central perspective. His interest in

these themes is documented in numerous works. Printed graphics also

provided him with undreamed of opportunities for experimentation free of

the prescriptions relating to commissioned works.

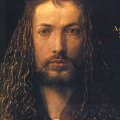

For Durer, the year of 1500, which was expected to signal the end of the world, started with the preparation of his Self-Portrait in a Fur-Collared Robe, his last and most famous self-portrait which is now in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich. In it he included the sum of his artistic and humanist ideas and, at the same time, introduced a new period in his creative work. Since he gives his age as being 28 in the inscription, the painting must have been created before 21 May, Durer's birthday. Karel van Mander reports that he saw the picture in Nuremberg in 1577 and held it in his hand. Durer retained possession of the painting during his lifetime, but after his death it ended up in the "upper regimental chamber" of the Nuremberg town hall which was used as a sort of art gallery. In 1805 it was finally acquired by the royal collection in Munich. Without understanding the humanist content of the panel, one would assume from a modern perspective that Durer's self-portrait had a provocative effect at the time, since for the first and last time in Western art history an artist was portraying himself in the same style, in terms of composition and type, as Christ. Such a strict frontal view had until then been reserved for depictions of Christ, and portraits traditionally made use of a half or three-quarter profile view. Durer used the geometric scheme of proportions in his self-portrait on which depictions of Christ had been based, and which had been reserved for this purpose, since Byzantine art. This was the scheme by which pictures of Christ appeared to be "vera icon," true portraits of the Savior. It was in this sense that the form of the self-portrait was repeated a century later in Georg Vischer's painting of Christ and the Adulteress, which he created for the Bavarian Elector Maximilian I.

Although Durer realistically reproduced his own physiognomic features such as bis large nose and differently sized eyes, the fine, illusionistic manner of painting gives the self-portrait an idealizing glow. Durer is clutching his smart fur coat with one hand, the position of which is reminiscent of Christ's hand raised in blessing. The eye is particularly significant, being the painter's second "tool" after his hand. Hence, a small window is reflected in the portrayed artist's iris, and this should be viewed not as a naturalistic depiction of the workshop window, but as an expression of the classical topos "oculi fenestra animae," the eye as a window to the soul, which Durer had presumably heard about from Konrad Celtis (1459-1508). The dark background helps us to concentrate on the figure of the artist. The inscription, "Albertus Durerus Noricus ipsum me proprus sic effingebam coloribus aetatis anno xxviii" (I, Albrecht Durer of Nuremberg, painted myself thus in everlasting paints at the age of twenty-eight years), emphasizes his intention to create a portrait for eternity.

Five epigrams praising Durer, written by the Nuremberg humanist Konrad Celtis, date from the same time; they are written in the same antiquated script as the inscription on the self-portrait and have a similar wording. In them, Celtis stressed Durer's creative powers by comparing him to Apelles and Phidias (5th century B.C.), two of the most famous classical artists. He also did not shy away from comparing him to the medieval philosopher Albertus Magnus (c. 1206 - 1280) and emphasized that God had given both similar creative powers. These sources prove that Durer, in his self-portrait, was expressing the God-given "natural" similarity of the artist to Christ brought about by his quality as a creator. We do not know for certain what the purpose of the portrait was. The fact that the painting remained Durer's property for the rest of his life suggests that it had a didactic function as a teaching aid for his students and as a showpiece for his clients. The importance of the unity of "Harmonia" and "Symmetria" emphasized by classical authors such as Cicero (106-43 B.C.), Lucian (120-180 A.D.) and Vitruvius is clearly reflected in this portrait. The strict frontal view also reminds us that sight was the sense that Durer valued the most highly, as can be deduced from the preface to his planned Treatise on Painting in 1512.

The color palette, limited to brown and gray tones, could possibly be an allusion to the writings of the classical author Pliny (23/24-79 A.D.), who reported that Apelles used a palette of four colors, and it was his masterly use of them that gave his paintings a special radiance. In this respect, Durer appears here as the new Christian Apelles who sees himself as a creator in the service of God and as such takes up a forward-looking position. An earlier interpretation connected the similarity to Christ in the picture with the desire to imitate Christ as promoted in the Imitation of Christ, a book that was widely available in the late Middle Ages and written by the religious mystic Thomas a Kempis (1379/1380-1471).

The Self-Portrait in a Fur-Collared Robe of 1500 is both the climax and the conclusion to Durer's three painted self-portraits.

This painting, produced at a turning point in his creative work, includes humanist ideas. Durer was also attempting to place his other works of the period on a new footing in the sense of a reformation of art in imitation of classical artists. During the following four years, numerous studies on human proportions were produced, encouraged by his meeting with the Italian artist Jacopo de Barbari (c. 1440- c. 1515), who he met in Nuremberg in 1500 and who spurred him on to study the canon of ideal proportions according to Vitruvius. This theme was to occupy Durer for the rest of his life and finally resulted in the Four Books on Human Proportions which were published posthumously. This is the context within which his efforts to depict the ideal proportions of a horse should be seen, which manifests itself in various drawings and copper engravings such as the Large Horse and the Small Horse and reached perfection in Durer's masterly engraving of Knight, Death and the Devil. In the third chapter of Vitruvius' famous treatise de architeetura, he considers human proportions and central perspective. This, and the rediscovery of a classical statue of Apollo in Rome as well as Jacopo de Barbari's copper engraving of Apollo and Diana, exerted considerable influence on the so-called Apollo Group and other studies on male and female proportions in imitation of the classical era that were finally to culminate in his famous masterpiece, the engraving of Adam and Eve. Durer believed that classical artists had possessed the secret that he spent his entire life trying to track down "with compass and spirit level." Both secular and sacred themes were a pretext for him to capture ideal depictions of nudes in printed graphics. An example of his studies of the proportions of the female body is the copper engraving that was created in about 1501 or 1502, Nemesis or Good Fortune. In technical terms, Durer refined the unusually large copper engraving even further. The larger lines are subdivided two or three times, and the use of double cross-hatchings is further improved, giving the sheet a high degree of material density. The depicted theme is derived from a Latin poem by the Florentine humanist and Neoplatonist Politian (1454 - 1494), published in his book Manto which appeared in 1499 and with which Durer probably became acquainted in the library of his friend Willibald Pirckheimer. The poem combines Fortuna, the goddess of Fate, with Nemesis, the goddess of Revenge.

In Durer's depiction, a winged female figure is floating on a globe high above the clouds. The landscape visible beneath is confirmed by one of Durer's watercolors that has since been lost. It is thought to be the small town of Klausen in the Eisack Valley in the Southern Tirol, Italy. The figure is holding a goblet and bridle in her hands, symbols of good and bad fortune. She appears to be standing still, only the fluttering cloth and uncertain standing position reveal motion. Panofsky put it very aptly: "The mighty figure is depicted in a geometric side elevation, like a diagram in a treatise on anthropometry."

This was the first figure to which Durer had applied Vitruvius' canon of proportions, in which individual parts of the body are proportioned in a particular way relative to the size of the body. Studies of proportions confirm that Durer started by inscribing a measurement scheme on his figures which included all the details of the body. The result, as is also the case here, appears rather artificial.

The masterly engraving of Adam and Eve, dating from 1504, must be considered the conclusion to his studies of proportion. It is a famous engraving in which his efforts to achieve the classical ideal of beauty were combined with Old Testament, Christian themes. The copper engraving was preceded by preparatory studies. Adam and Eve appear to be two independent studies of the ideal proportions of man and woman. The classical pose is a result of Durer's familiarity with classical sculpture. The figure of Adam is related to earlier dated drawings of Apollo, Asdepius and Sol, and Eve to such as the Medici Venus. The first human couple is standing before a dark forest. Their bodies are lit by light falling from the left. The centrally placed tree compositionally separates the couple who are facing each other. The surrounding flora and fauna symbolically emphasize the typological relationship between the Old and New Testaments. The mountain ash, the Tree of Life in front of which Adam is positioned, stands opposite the Tree of Knowledge which, complete with the diabolical serpent, is assigned to Eve. The parrot appears as a symbol of Mary and sign of the overcoming of sin by Mary, the second Eve. The animals in the foreground are references, in keeping with scholastic teachings, to the link between the Fall of Man and the four humors. According to them, the constitution and soul of Man before the Fall were in perfect harmony, but afterwards illness, death and vice entered his life. The soul was divided up into the four humors, embodied by the four animals depicted here.

The elk represents the melancholy, the cat the choleric, the ox the phlegmatic and the hare the sanguine humor. The cat and mouse symbolize the tense relationship between the genders, and the ibex on the rocky peak in the background is a symbol of the first human couple's disbelief when they disobeyed God's law and sinned. Durer self-confidently signed the work with the Latin inscription "Albertus Durerus Noricus faciebat 1504" (this was created by Albrecht Durer of Nuremberg in the year of 1504) on the so-called "cartellino," a small plaque hanging in the tree. This type of signature had already been pioneered by the Italian artist Antonio Pollaiuolo, as had the arrangement of various nudes in front of a half shaded background.

The small copper engraving of the Nativity, also created in 1504, was a reformulation of the Paumganner Altar produced shortly beforehand, and the result of Durer's study of spatial composition using central perspective, again based on Italian models.

Mary is shown in an old half-timbered building symbolizing the ruin of the Old Covenant, kneeling in prayer before the Child who has come as a symbol of the New Covenant to replace the old. Joseph, separated from this scene, is fetching water from the well. In contrast to the shepherd kneeling in the background, he does not appear to have noticed the holy events. In the background, in miniature, the Annunciation to the shepherds can be seen. In this sheet, "the stage is almost more important than the actors," as Panofsky stated, and the events are subordinate to the struggle for compositional unity in the sense that every detail has to fit in to the perspective of converging lines.

At the same time the twelve drawings of the famous Green Passion in the Albertina in Vienna were created, named after the olive green primed paper medium. For the first time, Durer used white highlights, creating dramatic lighting effects. The use of black ink increased the effect. The sheets already anticipate Durer's Engraved Passion, dating from just a few years later. The drawings were presumably used as sketches for twelve panels in the castle and university chapel in Wittenberg, commissioned by Elector Frederick the Wise.

Principal painted works

The second Italian journey

"That which I liked so much eleven years ago, I do not like

any more;" Durer to Pirckheimer in a letter dated 7 February 1506

"That which I liked so much eleven years ago, I do not like

any more;" Durer to Pirckheimer in a letter dated 7 February 1506

In contrast to the first Italian journey, the only evidence of which is the sentence dating from 1506 quoted above, Durer's second period in Italy is documented in ten letters written to his friend Willibald Pirckheimer, who also made the journey financially possible. Eight of these letters were discovered in 1748, when renovation work revealed a hollow wall in the family chapel in the house belonging to Pirckheimer's brother-in-law, Hans Imhoff (1488-1526). As the first existing personal private letters from an artist to his friend in the history of German art, they are extremely significant. Other letters that no longer exist and which Durer wrote to his wife and mother are mentioned in this correspondence.

It is thought that the reasons for Durer's second departure for Venice were partly due to the desire to escape a new outbreak of the plague in Nuremberg, and partly to do with matters of copyright, for Giorgio Vasari mentions in his Lives of the Artists that Durer came to Venice in order to initiate proceedings against the artist Marcantonio Raimondi (1480-1530). Marcantonio had seen prints by Durer on sale in St. Mark's Square in Venice, and had been extremely enthusiastic about them. Subsequently, he engraved copper copies of Durer's woodcuts and added his own monogram to them. It was the first trial in German art history to revolve around the protection of copyright. Durer's achievement was that the Signoria, the city government of Venice, forbade Marcantonio to add his monogram to the copies. However, these forgeries also prove just how highly regarded Durer was and internationally renowned at this time. In Italy, Durer's works were already being imitated in a big way by painters, copper engravers and ceramists. Copper engravings such as The Prodigal Son and the Madonna with the Monkey were frequently used as models, particularly because of their successful composition and finely executed, "natural" background landscapes.

Durer was mainly accepted by Italian artists as a graphic artist, less so as a painter. The criticism leveled at him was that he did not imitate the classical period enough. But barely a year later, Durer proudly reported to Willibald Pirckheimer in a letter that he had silenced those who did not think him a good painter in his major commissioned work for the German commercial brotherhood of San Bartolommeo, the Feast of the Rose Garlands : "jch hab awch dy moler all gschilt, dy do sagten, jm stechen wer ich gut, aber jm molen west ich nit mit farben vm zw gen" (I have also silenced all the painters who said, I was good at engraving, but I did not know how to work with paints).

But his own artistic judgment also altered: Things that had enthused him on his first visit to Italy now no longer impressed him. Equally, his opinions about his colleagues changed. Jacopo de Barbari, whom he had previously respected so much, could now no longer withstand his criticism. His judgment about the old Giovanni Bellini, who he also mentioned in his letters to Pirckheimer, was rather different. He and the old master behaved with respect towards each other and always praised each other in public.

All the paintings created during these years reveal Durer's endeavors to combine Italian feelings about color and composition with his own pictorial ideas and to develop his own personal style.

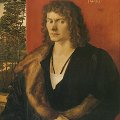

The Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman in the costume typical of the city is the first painting that Durer produced shortly after his arrival in Venice in 1505. The figure of the young, unidentified woman stands out against the dark background. She is wearing a bonnet interwoven with gold thread on her reddish hair. Her face and hair are surrounded by gentle white highlights. The emphasis in the portrait is not on creating a picture of ideal beauty but rather on depicting individuality. The full, irregular lips, the large nose and high forehead underline the impression of personal proximity. The summary execution of the dress indicates that Durer did not complete the portrait. The type of portrait, with the depicted woman gazing to the right against a dark background, is characteristic of portraits created during this time.

Durer summed up his experiences with Italian Renaissance art in the composition and colors of his main work during these years, created in 1506 and known since the 19th century as the Feast of the Rose Garlands. The large community of German merchants living in the "Fondaco dei Tedeschi," the German warehouse by the Rialto, commissioned him to produce this panel. In a letter dated 6 January 1506, Durer told Willibald Pirckheimer that he had been commissioned by the "Tewczschen" to paint an altar-piece for their church of San Bartolommeo. It has not been shown beyond doubt just who precisely was the donor and commissioner of the altar painting. It is probable that the artist was commissioned by the community of German merchants belonging to the German Brotherhood of the Rosary, founded in Venice in 1504 and attached to San Bartolommeo, a church in which sermons were given in German.

A fee of 110 Rhenish florins was agreed for the completion of the "Tewczsche thaffel," as Durer always called the picture. The deadline had been fixed: the panel should "ein monett nach ostern awff dem altar stehen" (stand on the altar one month after Easter.)

Durer prepared the picture very carefully in a large number of drawn studies, 22 in all. Each of these studies is an independent work of art of the highest level.

Durer's altar painting is a brilliant conglomeration of German Dutch, Flemish and Italian stylistic features. The shape of the altarpiece, without wings, is derived from Venetian types of pictures and formats. These are also the source for the method of composition - the type known as Sacra Conversazione comes to mind - as well as the integration of the central group of figures into a triangle.

The influence of Bellini's rich and shining colors is evident here in the symmetrical composition; a concrete model is the votive picture of Doge Agostino Barbarigo (died 1571). The precise recording of materials is reminiscent of works by Flemish artists such as Jan van Eyck, and the crowd of figures of the German tradition of altars full of figures such as those painted by Stefan Lochner (1410 - 1451). However, the depicted theme reminds us that Durer's teacher, Michael Wolgemut, had also created an altar for the Brotherhood of the Rosary in the Nuremberg Dominican church of St. Marien, and Durer must certainly have been familiar with it.

The theme is part of the German pictorial tradition of the Brotherhoods of the Rosary: Mary, crowned by angels, the Christ Child and St. Dominic are handing out rose garlands to mankind, led by the pope and emperor. The objects of homage here were both Mary and the Rosary, and the secular and ecclesiastical authorities of the Germans.

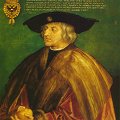

The symmetrical composition is supported by framing trees on the right and left edges of the picture. Mary, enthroned in the center beneath a baldachin held by an angel, and dressed in Venetian costume, is crowning Emperor Maximilian on her left as the leader of the secular ranks. The Christ Child in her arms is about to put a rose garland on the pope, the head of the spiritual ranks. The events are being given a musical accompaniment by an angel at Mary's feet who is playing a lute. The counterpart to the coronation of the two highest representatives of the State and Church is the Coronation of the Virgin. Flying putti distribute rose garlands to the people gathered to the right and left of the throne. In preceding illustrations, such as a woodcut accompanying a written work about the Brotherhood of the Rosary written by the Dominican monk Jakob Sprenger (active from c. 1468 - c. 1494/1498), it was the faithful who brought rose garlands to the Madonna. Behind the pope, St. Dominic appears, dressed in his order's habit, and he is holding a white lily in his hand, the symbol of the virginity of Mary.

The execution of material details such as the crown meant for Mary, the brocade pluvial worn by the pope and other garments, and the depicted landscape are of such exquisiteness that it creates the impression that Durer had gone out of his way to convince every single one of his critics.

The numerous portraits in the retinues accompanying the central group document the clients' intentions to have a piece of artistic evidence created of the community of German Christians in Italy. Some of the portraits, probably members of the German colony in Venice, can be identified with absolute certainty. But there are also a number of invented portraits amongst them. The portrayal of the pope, the original version of which has been handed down in a drawn study, cannot however be definitely identified as a portrait of Julius II. The pope and emperor are depicted traditionally in keeping with the theory of the two powers, temporal and spiritual, who were the heads of the Civitas Dei, the Christian community. The coronation of the emperor, whose features Durer had previously only known from a drawing by the Augsburg master Hans Burgkmair (1473 - 1531), occupies a central position in the scene. Although Maximilian I was not yet emperor at the time the picture was created, he is already portrayed as such here. As Doris Kutschbach has recently expounded, this can be interpreted as a political intention, an appeal from the German merchants to the city of Venice not to block the emperor's coronation. This was because the French and Venetians were resisting Maximilian's plans to have the pope crown him emperor of Germany in Rome by forbidding him passage through their territories. The pope and emperor are joined by the various representatives of the ecclesiastical ranks, cardinals and bishops, priests and monks, and the secular ranks, knights and merchants, artists and craftsmen.

To the right of the picture, in front of a tree, the artist himself is depicted with a piece of paper in his hand. He is gazing directly at the observer. Dressed in a smart fur cloak with an alpine landscape behind him, he self-confidently identifies himself as the gentleman, which he was considered to be and treated as in Venice. The conspicuously displayed sheet in his hands bears the inscription "exegit quinque/mestri spado Albertus/Durer Germanus/. M.D.VI." (Albrecht Durer, A German, created this in the space of five months. 1506).

Next to Durer, away from the main events, stands a man who is still proving difficult to identify due to a lack of preliminary sketches. It has been thought that this is the humanist Konrad Peutinger (1465-1547), who was an imperial advisor, as he also acted as an intermediary between the emperor and artists. Much of the original effect of the transparent paints and illusionistic recording of materials has probably been lost, for when the painting was moved from Venice it was badly damaged and was overpainted in many places.

The painting also played an important role for Durer, as he had succeeded in disproving his opponents' opinions about his achievements in painting. Even the Doge Leonardo Loredano (1431-1521) and Antonius of Surianus, the patriarch of Venice (died 1508) came in person in order to view the picture. Observers were particularly impressed by the careful application of the paint and the choice and harmony of the color values.

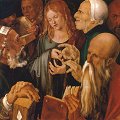

Durer incorporated a variety of ideas in this picture. The gesture language of the hands is new, clarifying the dispute between Christ and the bad doctor standing directly next to him, and this is a method of depiction which is more frequently encountered in Italian pictures of debating doctors. This play of hands may have been inspired by Giovanni Bellini's painting Lamentation over the Dead Christ. The doctors seem to ignore Christ as they talk and look around just as much as they avoid visual contact with each other. Each of the figures has a different position of the head, and this produces a rhythmic overall image. Since the Middle Ages ugliness had been equated with wickedness. The exaggerated depiction reminds us that Durer may already have been familiar, in Florence, with the caricatures produced by Da Vinci, the famous Italian artist, architect and natural scientist. His treatise on painting, the Trattato della Pittura, contains a rule recommending the contrast of absolute beauty and extreme ugliness.

The reproduction of rhetorical gestures and the arrangement of the figures in the picture reveals the influences of northern Italian half length portraits such as those by Andrea Mantegna, and a Venetian compositional scheme which shows Christ in the center of the picture surrounded by a group of half length figures. Durer's signature appears on a bookmark sticking out of an open book, with the addition of "opus quinque dierum," a reference to the fact that the work was produced in the remarkably short time of five days.

A finely executed large sheet of paper that was later divided in the middle originally connected the two preliminary studies for the heads of the lute-playing angel in the Feast of the Rose Garlands and that of the twelve year-old Christ. These brush drawings with white highlights were produced by Durer on blue Venetian paper with white and black watercolors, and this gives the light and dark effects a particular impact. He had become familiar with the technique in Italy and perfected it to a degree that almost exceeded the ability of its inventor.

The Madonna with the Siskin was painted by Durer at the same time as the Feast of the Rose Garlands and Christ among the Doctors. It achieved considerable popularity due to its majestic type of composition and the shining colors which are interrelated with the picture's humanly natural and emotional values. The picture of the Madonna is part of the tradition of Giovanni Bellini's monumental paintings and, in terms of style, is directly connected to the Feast of the Rose Garlands. Mary, in Venetian costume and crowned by putti, is enthroned before a red curtain, to the side of which we can see out onto an alpine landscape.

In contrast to early depictions of the Madonna influenced by Schongauer, the group of figures is moved close to the front edge of the picture. The small St. John the Baptist, assisted by an angel who is holding the cross-shaped staff as a symbol of Christ's Passion, is offering Mary lily of the valley flowers, symbols of her virginity. Jesus, holding a pacifier in his right hand, is playfully balancing the siskin, a symbol of the sinful souls redeemed by Christ, on his elbow. The book on which Mary is leaning her arm is an allusion to the Mother of God as the "sedes sapientiae," the seat of eternal wisdom. The oak leaf crown above her head fits in with this subject. The piece of paper lying on the table bears Durer's monogram and the inscription: "Albert(us) durer germanus/faciebat post virginis/ partum 1506" (The German Albrecht Durer made this after the Virgin gave birth 1506).

In terms of style and color, it is clear that the Feast of the Rose Garlands, Christ among the Doctors and the Madonna with the Siskin were all created at about the same time. They document Durer's ability to combine Italian models with his own pictorial ideas.

By the beginning of 1507, Durer had probably already returned to Nuremberg. He was in a good financial position after his successful time in Venice, was able to pay off his debts to Pirckheimer and, from the heirs of the astronomer Bernhard Walter (c. 1430-1504) he bought the building by the Tiergartner Gate that was to gain fame as Durer's house.

The lack of theoretical treatises on the nature of painting caused Durer, from 1508 onwards, to direct his attention to writing a book on painting which was given the interim title of "speis der maler knaben," but we only know of its planning from a few scattered notes. It was intended to be a textbook for his assistants and apprentices, and in addition to Durer's own knowledge about geometry, perspective and color also provided advice on personal hygiene, morals and human problems.

During the ensuing years, the Feast of the Rose Garlands, Durer's first major painted work, was followed by further masterpieces.

Shortly after his return from Italy, Durer was commissioned to create a painting of the Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand for his patron, the Elector Frederick the Wise. The work was meant for the chamber of relics in the Wittenberg castle chapel which housed a large collection of relics, including those of the 10,000 Christian martyrs. Durer had already dealt with the theme in an earlier woodcut which was based on the same preliminary studies as the painting. In the preparatory drawing, Durer still planned the picture to have a horizontal format. However, the choice of a vertical format, presumably a requirement on the part of the client, meant that in the end the composition and arrangement of the figures once more coincided with those of the woodcut. As in the painting of the first man and woman, Durer added the word "alemanus" to his name: Albrecht Durer the German. Numerous horrendous scenes of the martyrdom of the 10,000 Christian warriors and their leader Achatius on Mount Ararat are visible amidst a steep rocky landscape. The action develops horizontally in stepped picture strips. In addition to the powerful blue, the main colors are brown, red and green tones. The artist has depicted himself in the center of the picture, gazing out at the observer. He is deep in conversation with the humanist Konrad Celtis, who was held in equally high esteem by the Elector. In the sense of platonic love in accordance with the notions of the Italian humanist Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499), they are intently watching the martyrs' sufferings. Their dark clothing distinguishes them from the rest of the event which is depicted in shining colors. While Durer has been considered to be dressed in mourning in honor of the dead man, the robes of his companion have been interpreted as those of the professor of poetics at the University of Vienna. The little scene is interpreted as a recommendation for the soul of the dead humanist to the 10,000 martyrs. The panel fulfills two functions. On the one hand, it is a devotional picture relating to the relics belonging to the Elector, and on the other hand, it is a memorial picture commemorating dead humanist. There had been relations between the client, painter and humanist for some years, so that the Elector must have been aware of the double meaning of the picture. The painting was held in high esteem by Frederick the Wise and his nephew and successor Johann Frederick of Saxony (1503 - 1554). The latter is even supposed to have asked for it during his imprisonment in Brussels.

At the same time as the Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand, Durer was working on an extensive altar for the wealthy Frankfurt cloth merchant Jacob Heller (c. 1460-1522), another important client who had heard of Durer's outstanding achievement in the Feast of the Rose Garlands in Venice. He commissioned Durer to produce a winged altar in three sections, meant to be dedicated to St. Thomas Aquinas, for the Dominican church in Frankfurt am Main. Nine existing letters document the difficult relationship between client and artist. The central altar picture was intended to be a new iconographical form of picture combining the Coronation of the Virgin with the Assumption, and the side wings were to depict scenes of martyrdom, donor portraits and standing saints. The central panel was completed by 1509. Matthias Grunewald (c. 1460/1480-1528) painted two additional outer side panels with standing saints in grisaille. As copies of the central panel and wings from Durer's workshop prove, the Heller Altar was, together with the Paumgartner Altar, one of Durer's most extensive altarpieces. In 1729 the central panel, a pale reflection of which is provided by a copy dating from 1614, was destroyed in a fire in the Munich residence. Eighteen preliminary studies, brush drawings on green, blue or gray primed paper which Durer produced for this work influenced by Italian models, survived and convey an impression of what must have been a magnificent painting.

It was probably in 1508 that Durer was commissioned to produce another altar painting, the Adoration of the Trinity, by Matthaus Landauer (died 1515), a Nuremberg metal dealer. The picture was intended for the Chapel of All Saints in the home that Landauer had founded for old craftsmen who had become impoverished through no fault of their own, and it was completed in 1511. Durer designed the picture and frame as an artistic and iconographical whole. In keeping with Italian models, he chose a single panel, the relatively small size of which also differs from large altarpieces. At the request of the client, the work was carried out in a particularly lavish manner: the gold-colored sections were executed with real gold. A carved frame with Christ sitting in judgment and Mary and St. John in prayer opens up the view, in the manner of an eschatological prelude, of a heavenly vision comprising a gathering of all the saints around a depiction of the Holy Trinity. This vision heralds what is awaiting each individual after the Last Judgment in the City of God. In the earthly zone, an extensive river landscape, impossible to identify beyond doubt, is also a symbol of the real world.