Albrecht Durer

Albrecht Durer, a German painter and printmaker.

Durer is generally regarded as the greatest Northern Renaissance artist. His famous paintings have been the subject of

extensive analysis and interpretation. His watercolours

mark him as one of the first European landscape artists, while his

ambitious woodcuts revolutionized the potential of that medium.

Durer's introduction of classical motifs into Northern art, through

his knowledge of Italian artists and German humanists, have secured

his reputation as one of the most important figures of the Northern

Renaissance. This is reinforced by his theoretical works which involve

principles of mathematics, perspective and ideal proportions. The

quality and wide range of his works and themes, both in terms

of content and formal aspects, are astonishing. Though his paintings

were normally produced as the result of a commission - his two main

areas of focus were portrait painting and the creation of altar pieces

and devotional pictures - Durer enriched them with unusual pictorial

solutions and adapted them to new functions.

After his death, Durer remained one of the most highly regarded of

artists for centuries, representing the process of transition from the

late Middle Ages to the Renaissance in Germany.

Albrecht Durer, a German painter and printmaker.

Durer is generally regarded as the greatest Northern Renaissance artist. His famous paintings have been the subject of

extensive analysis and interpretation. His watercolours

mark him as one of the first European landscape artists, while his

ambitious woodcuts revolutionized the potential of that medium.

Durer's introduction of classical motifs into Northern art, through

his knowledge of Italian artists and German humanists, have secured

his reputation as one of the most important figures of the Northern

Renaissance. This is reinforced by his theoretical works which involve

principles of mathematics, perspective and ideal proportions. The

quality and wide range of his works and themes, both in terms

of content and formal aspects, are astonishing. Though his paintings

were normally produced as the result of a commission - his two main

areas of focus were portrait painting and the creation of altar pieces

and devotional pictures - Durer enriched them with unusual pictorial

solutions and adapted them to new functions.

After his death, Durer remained one of the most highly regarded of

artists for centuries, representing the process of transition from the

late Middle Ages to the Renaissance in Germany.

Altar and religious paintings by Durer

- Christ as the Man of Sorrows (1493)

- St. Jerome (1521)

- Virgin and Child (1496)

- The Seven Sorrows of the Virgin, Mother of Sorrows (1496)

- The Seven Sorrows of the Virgin, The Flight into Egypt (1496)

- Seven Sorrows of Maria, Christ on the Chross (1497)

- Lot Fleeing with his Daughters from Sodom (1498)

- Madonna and Child (Haller Madonna) (1498)

- Lamentation for Christ (Detail) (1503)

- Lamentation for Christ (1503)

- Paumgartner Altar (Center Panel) (1498)

- Paumgartner Altar (Left Panel) (1498)

- Paumgartner Altar (Right Panel) (1503)

- Paumgartner Altar (Detail of Right Panel) (1503)

- Adoration of the Magi (1504)

- Job (1503)

- Two Musicians (1504)

- Christ among the Doctors (1506)

- Feast of the Rose Garlands (Detail) (1506)

- Feast of the Rose Garlands (Left) (1506)

- Feast of the Rose Garlands (1506)

- Madonna with the Siskin (Detail 3) (1506)

- Madonna with the Siskin (1506)

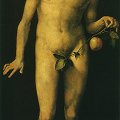

- Adam (1507)

- Eve (1507)

- The Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand (Detail 2) (1508)

- The Martydom of the Ten Thousand (1508)

- Heller Altar (Detail) (1509)

- The Adoration of the Trinity (Detail) (1511)

- The Adoration of the Trinity (Detail 2) (1511)

- Madonna of the Pear (1512)

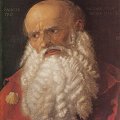

- The Apostle James the Elder (1516)

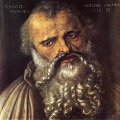

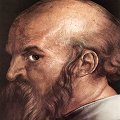

- The Apostle Philip (1516)

- The Madonna of the Carnation (1516)

- St. Anne with the Virgin and Child (Detail) (1519)

- St. Anne with the Virgin and Child (1519)

- Madonna and Child with the Pear (1526)

- The Four Holy Men (John the Evangelist and Peter) (1526)

- The Four Holy Men (Mark and Paul) (1526)

- The Four Holy Men (Detail 3) (1526)

Christ as the Man of Sorrows (1493)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Christ as the Man of Sorrows for your computer or notebook. ‣

This work depicts Jesus after he had been scourged and mocked by the

soldiers, just before he was led away to be crucified. Jesus bleeds

profusely from his wounds and he holds the instruments used to beat him, a

three-knotted whip and bundle of birches. He wears the crown of thorns,

leaning his head on his right hand in a gesture of grief. His other hand

rests on a ledge, a pose which Durer often used to add a sense of depth to

a portrait. The face is painted with great realism. Set against a gold

background, Christ stares out of the picture, expressing resignation at

his fate.

a high-quality picture of

Christ as the Man of Sorrows for your computer or notebook. ‣

This work depicts Jesus after he had been scourged and mocked by the

soldiers, just before he was led away to be crucified. Jesus bleeds

profusely from his wounds and he holds the instruments used to beat him, a

three-knotted whip and bundle of birches. He wears the crown of thorns,

leaning his head on his right hand in a gesture of grief. His other hand

rests on a ledge, a pose which Durer often used to add a sense of depth to

a portrait. The face is painted with great realism. Set against a gold

background, Christ stares out of the picture, expressing resignation at

his fate.

This devotional panel was identified as a Durer in 1941 and although unsigned it is now widely accepted as a work by the young artist. It dates from his journeyman days and may well have been done in Strasbourg, probably in 1493 or early in 1494.

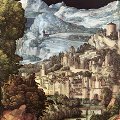

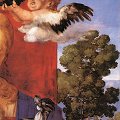

St. Jerome (1521)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

St. Jerome for your computer or notebook. ‣

St Jerome kneels as a penitent. In his right hand he holds the Bible,

which he translated into Latin, and in his left hand the stone which he is

using to beat his breast. His eyes stare upwards, beyond the small

crucifix stuck into the tree trunk. Wearing a blue gown, his red mantle and

cardinal's hat lie beside him on the ground. Behind is his faithful lion,

befriended after he had removed a thorn from its paw. In the background is

a landscape with dramatic rock formations, probably based on sketches that

Durer had made of the quarries near Nuremberg. The scene is lit by a

dramatic evening sky.

a high-quality picture of

St. Jerome for your computer or notebook. ‣

St Jerome kneels as a penitent. In his right hand he holds the Bible,

which he translated into Latin, and in his left hand the stone which he is

using to beat his breast. His eyes stare upwards, beyond the small

crucifix stuck into the tree trunk. Wearing a blue gown, his red mantle and

cardinal's hat lie beside him on the ground. Behind is his faithful lion,

befriended after he had removed a thorn from its paw. In the background is

a landscape with dramatic rock formations, probably based on sketches that

Durer had made of the quarries near Nuremberg. The scene is lit by a

dramatic evening sky.

The reverse of the panel depicts an apocalyptic celestial phenomenon, a red star-like light and a streaking golden disc. Although some scholars have considered it to be an eclipse or meteor, it is almost certainly a comet. Durer's image is probably derived from woodcuts of comets published in the Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493. A similar object to the one painted by Durer appears in the sky of his engraving of Melencolia I, made 20 years later.

Virgin and Child (1496)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Virgin and Child for your computer or notebook. ‣

Mary and the Christ Child sitting in her lap appear to be right in the

foreground of a space which opens to one side onto a bordering interior

courtyard. The baby reaches for his mother's hand and their eyes meet.

While the Madonna still owes much to the Late Gothic German type, the

Christ Child is reminiscent of Italian models. Half length figures such as

this early picture of the Madonna were widespread in Italy and the

Netherlands. The depiction of the space with the view to the side through

an arch is reminiscent of Flemish models, but the figural conception and

monumental triangular composition of the group of figures also relates to

Italy, in particular to the Madonna paintings by Giovanni Bellini. The

picture dates either from Durer's visit to Venice in 1494-5 or soon

afterwards in Nuremberg. It was discovered in the 1950s in the Capuchin

monastery of Bagnacavallo, near Ravenna, and this suggests that it was

painted in Italy where it has remained.

a high-quality picture of

Virgin and Child for your computer or notebook. ‣

Mary and the Christ Child sitting in her lap appear to be right in the

foreground of a space which opens to one side onto a bordering interior

courtyard. The baby reaches for his mother's hand and their eyes meet.

While the Madonna still owes much to the Late Gothic German type, the

Christ Child is reminiscent of Italian models. Half length figures such as

this early picture of the Madonna were widespread in Italy and the

Netherlands. The depiction of the space with the view to the side through

an arch is reminiscent of Flemish models, but the figural conception and

monumental triangular composition of the group of figures also relates to

Italy, in particular to the Madonna paintings by Giovanni Bellini. The

picture dates either from Durer's visit to Venice in 1494-5 or soon

afterwards in Nuremberg. It was discovered in the 1950s in the Capuchin

monastery of Bagnacavallo, near Ravenna, and this suggests that it was

painted in Italy where it has remained.

The Seven Sorrows of the Virgin, Mother of Sorrows (1496)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Seven Sorrows of the Virgin, Mother of Sorrows for your computer or notebook. ‣

This panel is a monumental picture depicting Mary as the Mother of

Sorrows. It was severely damaged in an attack when acid was thrown at it

in 1988, and ten years have been spent restoring it. It is the central

picture of the seven scenes from the Passion which are in the

Gemeldegalerie in Dresden. The work was presumably ordered by Elector

Frederick the Wise for the Wittenberg university chapel. Mary's arms are

crossed and she is looking up in suffering, while a sword that is

threateningly close to her heart is approaching, a symbol of her agonizing

pain caused by the sufferings of Christ, narrated on either side in the

scenes from the Passion. As a sign of her virginity, Mary is wearing a

white cloth and a heavy blue garment, the colour which refers to her

status as the Queen of Heaven.

a high-quality picture of

The Seven Sorrows of the Virgin, Mother of Sorrows for your computer or notebook. ‣

This panel is a monumental picture depicting Mary as the Mother of

Sorrows. It was severely damaged in an attack when acid was thrown at it

in 1988, and ten years have been spent restoring it. It is the central

picture of the seven scenes from the Passion which are in the

Gemeldegalerie in Dresden. The work was presumably ordered by Elector

Frederick the Wise for the Wittenberg university chapel. Mary's arms are

crossed and she is looking up in suffering, while a sword that is

threateningly close to her heart is approaching, a symbol of her agonizing

pain caused by the sufferings of Christ, narrated on either side in the

scenes from the Passion. As a sign of her virginity, Mary is wearing a

white cloth and a heavy blue garment, the colour which refers to her

status as the Queen of Heaven.

The Seven Sorrows of the Virgin, The Flight into Egypt (1496)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Seven Sorrows of the Virgin, The Flight into Egypt for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Flight into Egypt is one of seven scenes from the Life of Christ

which originally surrounded the large central panel of the Mother of

Sorrows. In the Gospel of St. Matthew (Matt. 2, 13-14), the event is

mentioned briefly, though narrated in more detail in the Apocrypha. King

Herod ordered that all newborn sons should be killed once he had found out

that a future king would be born in Judea. An angel conveys to Joseph

God's message to leave the town. Thus the Holy Family fled to Egypt.

a high-quality picture of

The Seven Sorrows of the Virgin, The Flight into Egypt for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Flight into Egypt is one of seven scenes from the Life of Christ

which originally surrounded the large central panel of the Mother of

Sorrows. In the Gospel of St. Matthew (Matt. 2, 13-14), the event is

mentioned briefly, though narrated in more detail in the Apocrypha. King

Herod ordered that all newborn sons should be killed once he had found out

that a future king would be born in Judea. An angel conveys to Joseph

God's message to leave the town. Thus the Holy Family fled to Egypt.

The group of figures, with Mary riding and holding the Christ Child and Joseph leading the ass, is arranged parallel to the picture in the foreground, an arrangement which is repeated in the later woodcut in the Life of the Virgin. In the foreground the path is stony, and in the background a rocky landscape is visible. The rock is a sign of a safe place of refuge, but can also be interpreted as a mariological and christological symbol: "The stone which the builders rejected, the same is become the head of the corner" (Matt. 21, 42). Both the composition and method of painting still owe much to the Late Medieval workshop tradition.

Seven Sorrows of Maria, Christ on the Chross (1497)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Seven Sorrows of Maria, Christ on the Chross for your computer or notebook. ‣

Durer's earliest known altarpiece may well have been commissioned by

Frederick the Wise for his palace church at Wittenberg. It was probably

ordered in April 1496, when Durer painted his portrait. A payment of 100

florins was made to the artist at the end of the year for the

altarpiece.

a high-quality picture of

Seven Sorrows of Maria, Christ on the Chross for your computer or notebook. ‣

Durer's earliest known altarpiece may well have been commissioned by

Frederick the Wise for his palace church at Wittenberg. It was probably

ordered in April 1496, when Durer painted his portrait. A payment of 100

florins was made to the artist at the end of the year for the

altarpiece.

The altarpiece was originally very large, nearly two metres high and nearly three metres wide. The right half, representing the Seven Joys of the Virgin, is now missing and only the left half of the Seven Sorrows survives. The central part of the surviving wing depicts the grieving Virgin after the Crucifixion, with a golden sword about to pierce her heart. Around the Virgin are seven smaller panels with detailed scenes from the life of Christ (anticlockwise from top left): the Circumcision, the Flight into Egypt, the 12 year-old Christ among the Doctors, the Bearing of the Cross, the Nailing to the Cross, the Crucifixion and the Lamentation.

The altarpiece was made in Durer's newly established workshop and although it was made to his design, some of it may have been painted by assistants. Durer's pen and ink study survives of the man drilling a hole in the Cross in the lower right panel of the Nailing to the Cross.

The whole altarpiece was acquired in the mid-sixteenth century by the artist Lucas Cranach the Younger (1515-86), whose distinguished father had served as court painter in Wittenberg. It was probably Cranach the Younger who sawed the work into separate panels. The panel of the grieving Virgin (which at some point was reduced in size by 18 centimetres at the top) is now in Munich and those of the Seven Sorrows are in Dresden. The right half of the altarpiece representing the Seven Joys is known only through copies.

Lot Fleeing with his Daughters from Sodom (1498)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Lot Fleeing with his Daughters from Sodom for your computer or notebook. ‣

This delightfully spontaneous panel depicts Lot and his two daughters

fleeing from the destruction of Sodom. In the story from Genesis, two

angels warn Lot that he should escape before God destroys the city for its

sins. Lot is told that his family must not look back, otherwise they will

be turned into pillars of salt.

a high-quality picture of

Lot Fleeing with his Daughters from Sodom for your computer or notebook. ‣

This delightfully spontaneous panel depicts Lot and his two daughters

fleeing from the destruction of Sodom. In the story from Genesis, two

angels warn Lot that he should escape before God destroys the city for its

sins. Lot is told that his family must not look back, otherwise they will

be turned into pillars of salt.

In Durer's panel, Lot leads the way, dressed in a warm fur-lined coat and a magnificent turban. He carries a basket of eggs and has a flask of wine slung over his shoulder on his stick. His two daughters follow several paces behind, one bearing a bundle on her head and the other with an elegant casket and a distaff and yarn. Far behind them, near the towering rocks, is Lot's wife, transformed into a brown pillar of salt. In the distance the town of Sodom explodes with brimstone and fire, huge columns of smoke belching up into the sky. Gomorrah, in the far distance, suffers a similar fate.

This depiction of Lot's flight is not the main picture, but the reverse of a panel of the Virgin and Child. The two sides are quite different, not only in subject-matter but also in style. The Lot panel is painted in a loose, spontaneous manner, whereas the Virgin and Child is much more finely worked. However, Durer must have intended them to be seen together. The panel was painted for the Nuremberg merchant family of Haller, whose arms appear in the bottom left corner of the panel of the Virgin.

Virgin and Child at a Window was long assumed to be the work of the Venetian artist Giovanni Bellini, because of its composition and colouring. In 1934 it was identified as a Durer, painted about three years after his return from Venice. It was bought by Baron Heinrich von Thyssen-Bornemisza, who owned it until 1950.

Madonna and Child (Haller Madonna) (1498)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Madonna and Child (Haller Madonna) for your computer or notebook. ‣

Commissioned by the Haller von Hallerstein family, it is a Venetian

type Madonna, seemingly an homage to Giovanni Bellini. There is another

painting on the back of the panel.

a high-quality picture of

Madonna and Child (Haller Madonna) for your computer or notebook. ‣

Commissioned by the Haller von Hallerstein family, it is a Venetian

type Madonna, seemingly an homage to Giovanni Bellini. There is another

painting on the back of the panel.

This Madonna and Child, which manifestly follows the Venetian precedent of the close-up, half-figure portrait, was once thought to be by Bellini. To Durer, Bellini was an example of a painter who could make the ideal become actual. But Durer can never quite believe in the ideal, passionately though he longs for it. His Madonna has a portly, Nordic handsomeness, and the Child a snub nose and massive jowls. All the same, He holds His apple in exactly the same position as in Durer's great engraving of Adam and Eve, and this attitude is pregnant with significance. The Child seems to sigh, hiding behind His back the stolen fruit that brought humanity to disaster and that He is born to redeem. On one side is the richly marbled wall of the family home; on the other, the wooded and castellated world. The sad little Christ faces a choice, ease or the laborious ascent, and His remote Mother seems to give Him little help.

Beautiful though the work is in color, and fascinating in form, it is this personal emotion that always makes Durer an artist who touches our heart, somehow putting out feelers of moral sensibility.

Lamentation for Christ (Detail) (1503)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Lamentation for Christ (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

This scene is framed above by a beautiful landscape in which Jerusalem

can be seen off the lakeshore, atop a hill, in the foreground. Behind the

city is a mountain peak and a mountain range that disappear into the

background. The city, mountains, and lake are flooded with light. A thick

blanket of heavy black clouds that thins out just above the lake in the

back looms over the mountains. While the presence of the black clouds is

justified by the narration of the crucifixion ("and darkness came over the

whole land... while the sun's light failed," Luke 23:45), and the light is

explained by the words of the apocryphal gospel of Saint Peter when he

describes the position ("and the sun began to shine again ", 6:21), the

Jerusalem that appears in the painting - a city near water, with house,

towers, and fortification walls, lying against rocky mountains - is

decidedly an invented, Nordic city, which does not at all reflect the

actual appearance, well known at that time, of this blessed city.

a high-quality picture of

Lamentation for Christ (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

This scene is framed above by a beautiful landscape in which Jerusalem

can be seen off the lakeshore, atop a hill, in the foreground. Behind the

city is a mountain peak and a mountain range that disappear into the

background. The city, mountains, and lake are flooded with light. A thick

blanket of heavy black clouds that thins out just above the lake in the

back looms over the mountains. While the presence of the black clouds is

justified by the narration of the crucifixion ("and darkness came over the

whole land... while the sun's light failed," Luke 23:45), and the light is

explained by the words of the apocryphal gospel of Saint Peter when he

describes the position ("and the sun began to shine again ", 6:21), the

Jerusalem that appears in the painting - a city near water, with house,

towers, and fortification walls, lying against rocky mountains - is

decidedly an invented, Nordic city, which does not at all reflect the

actual appearance, well known at that time, of this blessed city.

Lamentation for Christ (1503)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Lamentation for Christ for your computer or notebook. ‣

The lamentation scene, composed of nine figures under the cross,

occupies almost the entire painting. This scene is framed above by a

beautiful landscape in which Jerusalem can be seen off the lakeshore, atop

a hill, in the foreground. Behind the city is a mountain peak and a

mountain range that disappear into the background. The city, mountains,

and lake are flooded with light. A thick blanket of heavy black clouds that

thins out just above the lake in the back looms over the mountains. While

the presence of the black clouds is justified by the narration of the

crucifixion ("and darkness came over the whole land... while the sun's

light failed," Luke 23:45), and the light is explained by the words of the

apocryphal gospel of Saint Peter when he describes the position ("and the

sun began to shine again ", 6:21), the Jerusalem that appears in the

painting - a city near water, with house, towers, and fortification walls,

lying against rocky mountains - is decidedly an invented, Nordic city,

which does not at all reflect the actual appearance, well known at that

time, of this blessed city. In the centre, one sees the door that opens

into the garden of Gethsemane. A little more ahead, on the right, is the

entrance to the tomb in the rock, through which one can spot the uncovered

sarcophagus. The first thing that strikes the spectator is the chorale

composition of the sufferers around the figure of Christ.

a high-quality picture of

Lamentation for Christ for your computer or notebook. ‣

The lamentation scene, composed of nine figures under the cross,

occupies almost the entire painting. This scene is framed above by a

beautiful landscape in which Jerusalem can be seen off the lakeshore, atop

a hill, in the foreground. Behind the city is a mountain peak and a

mountain range that disappear into the background. The city, mountains,

and lake are flooded with light. A thick blanket of heavy black clouds that

thins out just above the lake in the back looms over the mountains. While

the presence of the black clouds is justified by the narration of the

crucifixion ("and darkness came over the whole land... while the sun's

light failed," Luke 23:45), and the light is explained by the words of the

apocryphal gospel of Saint Peter when he describes the position ("and the

sun began to shine again ", 6:21), the Jerusalem that appears in the

painting - a city near water, with house, towers, and fortification walls,

lying against rocky mountains - is decidedly an invented, Nordic city,

which does not at all reflect the actual appearance, well known at that

time, of this blessed city. In the centre, one sees the door that opens

into the garden of Gethsemane. A little more ahead, on the right, is the

entrance to the tomb in the rock, through which one can spot the uncovered

sarcophagus. The first thing that strikes the spectator is the chorale

composition of the sufferers around the figure of Christ.

One subsequently perceives the landscape, almost as if it were a second component of the painting. At this point, the two components together make the visual field explode.

The image of the lamentation is from a Dutch, not a German, tradition. Durer interprets it in Italian terms, associating, in the composition of the scene, the figures three by three: Nicodemus, Magdalene, and Saint John the Evangelist align themselves in an ascending order under the cross. In the centre, the head of the Madonna, while she wrings her hands, is joined by the heads of the other two Marys, who cry with her, the three representing three ages of life.

Last is Joseph of Arimathea, who supports the body of Christ with the sudarium. The image of the body is particularly impressive for the deathly pale colour and for the complete abandon of the lifeless parts. Another Mary stands out for her clothing, fashioned from Durer's period. She is weeping while holding Christ's hand.

Thus, a triad is formed, be it with the head of Christ and the Madonna, or of Christ and Joseph of Arimathea. The impression of these different triads contrasts with the great chromatic variety of the clothing. However, the rhythm that characterizes the harmonious composition of the figures is not to be found in the colours, since the exaggerated dimensions of the ointment vases breaks the regularity of the proportions, which is otherwise fairly consistent.

The beauty of the work lies chiefly in the depiction of the individual physiognomies and in the gradation of pain: from Magdalene's tear-stained eyes, to the expression of muted and composed suffering of almost all the rest of the figures, to the absolute desperation, shown by the gesture and wailing of the woman next to the Madonna.

The scene with the body of the dead Christ opens up toward the spectator, so that he can directly participate in the lamentation, following the Mary, clad in Renaissance attire, who lovingly clutches the hand of Christ. Since the entire scene is illuminated by a limpid "new light," the suffering of the lamentation is accompanied by a feeling of comfort, a feeling that Durer makes delicately transpire from the John and Magdalene, whose hopeful gazes are turned toward this light. This, apparently, is the Christian message of the panel. According to an enduring medieval tradition, the figures of the donors are painted, kneeling at the bottom of the scene: on the right, the position of honour, the goldsmith Albrecht Glimm with his coat of arms and two sons; to the left, the late consort with her own coat of arms and daughter. A crown of thorns lies in the middle, between the two groups.

Paumgartner Altar (Center Panel) (1498)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Paumgartner Altar (Center Panel) for your computer or notebook. ‣

The central scene represents the Nativity. Mary and Joseph are kneeling

in the foreground of an architectural scene constructed according to the

laws of central perspective, which opens out to the rear onto a broad

landscape; next to them the numerous small figures of the donor family are

kneeling before the newborn Christ Child. From the back, two shepherds

seen in a perspectival foreshortening are climbing up to the place of

Christ's birth, and on the left two more are watching the events. The

centre of the composition are Mary and the Christ Child, and they are

additionally emphasized by the baldachin-like roof. The Star of Bethlehem

is emblazoned in the sky, and in the background an angel is announcing the

birth of the Savior to the shepherds.

a high-quality picture of

Paumgartner Altar (Center Panel) for your computer or notebook. ‣

The central scene represents the Nativity. Mary and Joseph are kneeling

in the foreground of an architectural scene constructed according to the

laws of central perspective, which opens out to the rear onto a broad

landscape; next to them the numerous small figures of the donor family are

kneeling before the newborn Christ Child. From the back, two shepherds

seen in a perspectival foreshortening are climbing up to the place of

Christ's birth, and on the left two more are watching the events. The

centre of the composition are Mary and the Christ Child, and they are

additionally emphasized by the baldachin-like roof. The Star of Bethlehem

is emblazoned in the sky, and in the background an angel is announcing the

birth of the Savior to the shepherds.

Paumgartner Altar (Left Panel) (1498)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Paumgartner Altar (Left Panel) for your computer or notebook. ‣

The side wings depict St. George on the left and St. Eustace on the

right, complete with their attributes on their banners as recorded in the

Legenda aurea.

a high-quality picture of

Paumgartner Altar (Left Panel) for your computer or notebook. ‣

The side wings depict St. George on the left and St. Eustace on the

right, complete with their attributes on their banners as recorded in the

Legenda aurea.

Standing in a stony wilderness in front of a dark background is the figure of St. Eustace. He was a Roman general in the army of Emperor Trajan's army who was converted to Christianity after seeing the crucified Christ in the antlers of a stag; he was to suffer a horrible martyr's death under the emperor Hadrian. According to the Nuremberg Chronicle, Durer endowed the saint with the features of the donor, Lucas Paumgartner.

Paumgartner Altar (Right Panel) (1503)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Paumgartner Altar (Right Panel) for your computer or notebook. ‣

The side wings depict St. George on the left and St. Eustace on the

right, complete with their attributes on their banners as recorded in the

Legenda aurea. St. George was a crusader and had liberated the Libyan town

of Silena from the dragon, while the Crucified Christ had appeared to St

Eustace in a forest in the antlers of a stag, thus converting him to

Christianity. The donors themselves appear in the form of their personal

saints. On the left, facing the central panel, Stephan Paumgartner appears

as St. George, and on the right Lukas Paumgartner appears as St. Eustace.

Both are wearing splendid knightly armor. They are Christian knights,

guards and protectors of the holy shrine, the Nativity of Christ in the

central panel where they appear once more as part of the group of the

donating family.

a high-quality picture of

Paumgartner Altar (Right Panel) for your computer or notebook. ‣

The side wings depict St. George on the left and St. Eustace on the

right, complete with their attributes on their banners as recorded in the

Legenda aurea. St. George was a crusader and had liberated the Libyan town

of Silena from the dragon, while the Crucified Christ had appeared to St

Eustace in a forest in the antlers of a stag, thus converting him to

Christianity. The donors themselves appear in the form of their personal

saints. On the left, facing the central panel, Stephan Paumgartner appears

as St. George, and on the right Lukas Paumgartner appears as St. Eustace.

Both are wearing splendid knightly armor. They are Christian knights,

guards and protectors of the holy shrine, the Nativity of Christ in the

central panel where they appear once more as part of the group of the

donating family.

Paumgartner Altar (Detail of Right Panel) (1503)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Paumgartner Altar (Detail of Right Panel) for your computer or notebook. ‣

The altar has the traditional shape of a winged altarpiece. The

outside, the weekday side, displays a workshop production of an

Annunciation and the former standing figures of saints Catherine and

Barbara. When opened, the magnificent colours of the Nativity are visible,

framed by saints George and Eustace.

a high-quality picture of

Paumgartner Altar (Detail of Right Panel) for your computer or notebook. ‣

The altar has the traditional shape of a winged altarpiece. The

outside, the weekday side, displays a workshop production of an

Annunciation and the former standing figures of saints Catherine and

Barbara. When opened, the magnificent colours of the Nativity are visible,

framed by saints George and Eustace.

This triptych was commissioned by the brothers Stephan and Lukas Paumgartner for St. Catherine's Church in Nuremberg. It may well have been ordered after Stephan's safe return from a pilgrimage to Jerusalem in 1498. The main panel depicts the Nativity, set in an architectural ruin. The left wing shows St. George with a fearsome dragon and the right wing St Eustace, with both saints dressed as knights and holding identifying banners. A seventeenth-century manuscript records that the side panels were painted in 1498 and that the two saints were given the features of the Paumgartner brothers (with Stephan on the left and Lukas on the right). This is the earliest occasion on which an artist is known to have used the facial features of a donor in depicting a saint. The exteriors of the wing panels were of the Annunciation, although only the figure of the Virgin on the left panel has survived.

On stylistic grounds, the Nativity was painted a few years later than the wings, probably in 1502 or soon afterwards. The tiny body of Christ is almost lost in the composition, surrounded by a swarm of little angels. Peering out from behind the Romanesque columns on the right are the ox and the ass, while opposite them on the left side are the faces of two shepherds. The composition, formed by the ruins of a palatial building, draws the eye towards the archway. Two other shepherds step up into the courtyard, the red and blue of their clothes echoing the colours of Joseph and the Virgin Mary. In the sky, an angel descends to reveal news of Christ's birth to another pair of shepherds tending their flock on the distant hillside. Although traditionally a night-time scene, it is brightly illuminated by a ball of light in the sky.

The small figures at the bottom corners of the central panel are the Paumgartner family with their coats of arms. They were painted over in the seventeenth century, when donor portraits went out of favour, and were only uncovered during restoration in 1903. On the left behind Joseph are the male members of the family, Martin Paumgartner, followed by his two sons Lukas and Stephan and an elderly bearded figure who may be Hans Schenbach, second husband of Barbara Paumgartner. On the far right is Barbara Paumgartner (nie Volckamer), with her daughters Maria and Barbara.

In 1988 this painting was seriously damaged by a vandal, along with the Lamentation for Christ and the central panel of The Seven Sorrows of the Virgin depicting the grieving Mary. Restoration of the Paumgartner Altarpiece and the Lamentation for Christ was completed in 1998 and work then began on the panel of the Virgin.

Adoration of the Magi (1504)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Adoration of the Magi for your computer or notebook. ‣

The elector Frederick the Wise of Saxony ordered this painting for the

Schlosskirche (the church in the castle) in Wittenberg. It was once

believed to be the central part of a polyptych, with, on the side wings,

the story of Job, in Frankfurt and Cologne. However, this hypothesis has

already been called into question. The elector of Saxony then donated the

painting to Emperor Rudolph II in 1603. An exchange with the Presentation

at the Temple by Fra Bartolomeo brought it in 1793 from the gallery in

Vienna to the Uffizi.

a high-quality picture of

Adoration of the Magi for your computer or notebook. ‣

The elector Frederick the Wise of Saxony ordered this painting for the

Schlosskirche (the church in the castle) in Wittenberg. It was once

believed to be the central part of a polyptych, with, on the side wings,

the story of Job, in Frankfurt and Cologne. However, this hypothesis has

already been called into question. The elector of Saxony then donated the

painting to Emperor Rudolph II in 1603. An exchange with the Presentation

at the Temple by Fra Bartolomeo brought it in 1793 from the gallery in

Vienna to the Uffizi.

This altarpiece was probably conceived without the lateral panels, in contrast with the actual practice in Nordic countries, and at variance with the situation of the Paumgartner altarpiece (Alte Pinakothek, Munich). Durer framed and delimited a large space by an architecture composed of arches of a very refined perspective. The three kings arrived at this slightly elevated space from the back and after having climbed two steps. A single figure, sharply foreshortened, followed in their footsteps from the distant background. Only the upper half of his body is shown where he now stands at the bottom of the two steps. He is Oriental and wearing a turban. The heavy traveling bag he holds probably contains precious gifts for the infant Jesus.

The Madonna is clad in azure clothes and cape, a white veil covering her head. She is holding out the infant, who is wrapped in her white veil, to the eldest king. He is offering the infant a gold casket with the image of Saint George, which the infant has already taken with his right hand. This is the only action that unfolds in the principal scene, except for the Oriental servant's gesture of putting his hand in his bag. All the other characters are motionless; immersed in thought, they look straight ahead or sideways, creating the effect of a staged spectacle set with immobile characters.

The architecture of the fictive ruins behind the Madonna is beautiful and imaginative. Durer had previously experimented with this design in drawings and engravings. The background is stupendous: the limpid sky, in which the cumulus clouds chase one another; the light Nordic city, climbing up the cone-like mountain; the road bending into the archway where people stop, following behind the three kings. These are represented with much imagination and variety, as far as the fashion and colour of their clothes and the differences in their expressions. In the far right are a lake and a boat.

This imagination and variety continue in the extraordinary depiction of the kings, in lavish clothing, with their precious jewels, and with the beautiful goblets and caskets that they bear as gifts. It is telling here that Durer was also an expert goldsmith. According to the Nordic tradition, also adopted previously by Mantegna in Italy, one of the kings is a Moor. The physiognomy of the young king with long blond curly hair, standing in the middle of the painting, bears, according to recent interpretation, a resemblance to a self-portrait of Durer.

Durer was passionately devoted to the study of animals and plants, which he reproduced faithfully from life. He often distributed these images in his landscape passages, and particularly in his drawings and engravings of the Madonna. We find some here as well: in the foreground, to the right, a flying deer, already known from various watercolours, which here symbolizes Christ; the plantain (plantago major) seen directly behind, whose healing properties were once much appreciated, recalls the spilled blood of Christ; in the foreground, now to the left, on the millstone beside the carnation, a small coleopterum surrounded by a few butterflies, the ancient symbol of the soul, which here may be a symbol of the resurrection.

The panel of the Uffizi represents the richest and most mature actualisation of all Durer's altarpieces, before his second trip to Italy, and therefore before the Feast of the Rose Garlands, painted in Venice (National Gallery, Prague).

Job (1503)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Job for your computer or notebook. ‣

The panel is a wing of the Jabach Altarpiece, named after one of its

previous owners. Originally, however, it was commissioned by Frederick the

Wise, elector of Saxony. Another panel in Cologne, depicting two

musicians, belongs to this altar, too. It is conceivable that these two

pictures are the results of sawing a larger one in two. Even though their

conditions differ, it is clearly visible that the background and the

horizon in both pictures match, and portions of the clothes of Job's wife

may be found in the picture of the two musicians. There is even a

sixteenth-century drawing which shows the two paintings as one

composition. The two pictures together may have constituted the centre

panel of a Job altar commissioned by Frederick the Wise to commemorate the

plague which ravaged the German lands in 1503.

a high-quality picture of

Job for your computer or notebook. ‣

The panel is a wing of the Jabach Altarpiece, named after one of its

previous owners. Originally, however, it was commissioned by Frederick the

Wise, elector of Saxony. Another panel in Cologne, depicting two

musicians, belongs to this altar, too. It is conceivable that these two

pictures are the results of sawing a larger one in two. Even though their

conditions differ, it is clearly visible that the background and the

horizon in both pictures match, and portions of the clothes of Job's wife

may be found in the picture of the two musicians. There is even a

sixteenth-century drawing which shows the two paintings as one

composition. The two pictures together may have constituted the centre

panel of a Job altar commissioned by Frederick the Wise to commemorate the

plague which ravaged the German lands in 1503.

It should be noted that there are scholars who have proposed that these two pictures used to form the two wing-panels of a triptych showing the Adoration of the Magi (now in the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence).

The altar, besides depicting Job as the patron saint of people suffering skin diseases, also points to his connection with music. On the first part of the painting we see the suffering Job cowering on a refuse heap while his wife drenches him with water. On the second part, the musicians are certainly the representatives of healing music. According to the medieval melotherapy, Job, who was devoted to music when he was healthy, should recover upon hearing the melody.

Two Musicians (1504)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Two Musicians for your computer or notebook. ‣

The panel is a wing of the Jabach Altarpiece, named after one of its

previous owners. Originally, however, it was commissioned by Frederick the

Wise, elector of Saxony. Another panel in Frankfurt, depicting Job and his

wife, belongs to this altar, too. It is conceivable that these two

pictures are the results of sawing a larger one in two. Even though their

conditions differ, it is clearly visible that the background and the

horizon in both pictures match, and portions of the clothes of Job's wife

may be found in the picture of the two musicians. There is even a

sixteenth-century drawing which shows the two paintings as one

composition. The two pictures together may have constituted the centre

panel of a Job altar commissioned by Frederick the Wise to commemorate the

plague which ravaged the German lands in 1503.

a high-quality picture of

Two Musicians for your computer or notebook. ‣

The panel is a wing of the Jabach Altarpiece, named after one of its

previous owners. Originally, however, it was commissioned by Frederick the

Wise, elector of Saxony. Another panel in Frankfurt, depicting Job and his

wife, belongs to this altar, too. It is conceivable that these two

pictures are the results of sawing a larger one in two. Even though their

conditions differ, it is clearly visible that the background and the

horizon in both pictures match, and portions of the clothes of Job's wife

may be found in the picture of the two musicians. There is even a

sixteenth-century drawing which shows the two paintings as one

composition. The two pictures together may have constituted the centre

panel of a Job altar commissioned by Frederick the Wise to commemorate the

plague which ravaged the German lands in 1503.

It should be noted that there are scholars who have proposed that these two pictures used to form the two wing-panels of a triptych showing the Adoration of the Magi (now in the Galleria degli Uffizi in Florence).

The altar, besides depicting Job as the patron saint of people suffering skin diseases, also points to his connection with music. On the first part of the painting we see the suffering Job cowering on a refuse heap while his wife drenches him with water. On the second part, the musicians are certainly the representatives of healing music. (The young drummer bears striking resemblance to the painter). According to the medieval melotherapy, Job, who was devoted to music when he was healthy, should recover upon hearing the melody.

The presence of a wind instrument, a type of trumpet, may suggest another association. In praise of the instruments, St. Augustine likened the brazen tone of the trumpet to the steadfastness of Job.

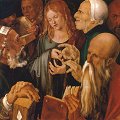

Christ among the Doctors (1506)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Christ among the Doctors for your computer or notebook. ‣

At the same time as the Feast of the Rose Garlands, Durer was working

on the painting of Christ among the Doctors. The theme derives from the

Gospel of St. Luke (Luke 2, 41-52).

a high-quality picture of

Christ among the Doctors for your computer or notebook. ‣

At the same time as the Feast of the Rose Garlands, Durer was working

on the painting of Christ among the Doctors. The theme derives from the

Gospel of St. Luke (Luke 2, 41-52).

On the bookmark at the bottom left of the panel, Durer has recorded that this picture was 'the work of five days', a pointed reference to his inscription on The Altarpiece of the Rose Garlands, the work of five months. Christ among the Doctors is not only a smaller panel, but the brushwork is much more spontaneous and the paint is applied with broad and fluid strokes. Despite Durer's statement about five days, he based it on a number of careful studies, including one of Christ's gesticulating fingers. Although not present on the original painting, two early copies of the panel have the word 'Romae' added to the inscription on the bookmark and this suggests that Durer visited Rome late in 1506. It may also be significant that the original painting was in Rome's Galleria Barberini until its acquisition by Baron Heinrich von Thyssen-Bornemisza in 1935.

The story recorded in the panel is of Christ's visit to Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem, where he debated with the learned Jewish doctors (or scribes). According to the Bible, this was the first occasion on which Christ taught. Durer's daring composition does not use the conventional temple setting which he earlier used in the lower left panel of The Seven Sorrows of the Virgin. Instead he gives a close-up view of the faces of six doctors crowding round the young Jesus. The elderly doctors, caricatured faces which may well have been influenced by Da Vinci, argue with Christ by quoting from the Scriptures and gesticulating. Christ, a sober boy of 12, quietly gestures with his fingers to make a point. Durer contrasts Christ's youthful hands with the gnarled fingers of the ugly old man with the white cap and a gap-toothed grin.

Feast of the Rose Garlands (Detail) (1506)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Feast of the Rose Garlands (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Feast of the Rose Garlands is undoubtedly the most important work

that Durer created during his sojourn in Venice and was the work that

ushered in the Renaissance. Durer was obviously aware of this, as his

letters and the painting itself demonstrate. The painting shows this in

the distinction he gives his self-portrait: in the top right, in front of

the typically German landscape passage at the foot of the mountains, with

his face framed by long blond hair, donning luxurious clothes - even a

precious fur cloak, in spite of the warm season - so as to be noticed

among the other characters. He alone has ostentatiously turned his gaze to

the spectator. Even the writing on the paper he holds is unusual for

Italy. It indicates not only the time of production (five months), but next

to his own name is the indication germanus. This detail was to distinguish

himself from his Venetian colleagues, who evidently held him in very high

regard, since even the doge and the patriarch came to his workshop to

admire his work.

a high-quality picture of

Feast of the Rose Garlands (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Feast of the Rose Garlands is undoubtedly the most important work

that Durer created during his sojourn in Venice and was the work that

ushered in the Renaissance. Durer was obviously aware of this, as his

letters and the painting itself demonstrate. The painting shows this in

the distinction he gives his self-portrait: in the top right, in front of

the typically German landscape passage at the foot of the mountains, with

his face framed by long blond hair, donning luxurious clothes - even a

precious fur cloak, in spite of the warm season - so as to be noticed

among the other characters. He alone has ostentatiously turned his gaze to

the spectator. Even the writing on the paper he holds is unusual for

Italy. It indicates not only the time of production (five months), but next

to his own name is the indication germanus. This detail was to distinguish

himself from his Venetian colleagues, who evidently held him in very high

regard, since even the doge and the patriarch came to his workshop to

admire his work.

The artist's companion is likely to be Leonhard Vilt, founder of the Brotherhood of the Rosary in Venice. The man in the far right, recognizable by the square he holds, is the architect Hieronymus of Augsburg, engineer of the new Fondaco dei Tedeschi (1505-8) after it was completely destroyed in a fire.

Inscription on the sheet in the artist's hand, monogrammed and autograph writing: EXEGIT QUINQUE MESTRI SPATIO ALBERTUS DURER GERMANUS MDVI. ('Albrecht Durer, a German, produced it within the span of five months. 1506.')

Feast of the Rose Garlands (Left) (1506)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Feast of the Rose Garlands (Left) for your computer or notebook. ‣

St Dominic is clearly the saint whom we see to the left of the Madonna,

since the institution of the rosary is attributed to him. For all the

others, many names have been proposed. However, the identifications are

still uncertain. The Madonna is enthroned in a field, beneath a green

canopy that cherubs hold up with ribbons. Other cherubs on little clouds

hold a crown of precious stones suspended above her head. At her feet

kneel the pope and the emperor, on the left and right, having placed before

themselves a tiara and a crown, respectively. And while the Madonna places

a garland of roses on the head of the emperor, the Blessed Child places an

identical one over the head of the pontifice. St. Dominic, in turn, crowns

a bishop. Behind the pope and the emperor, the patrons are arranged

symmetrically, some of whom, in both parts of the background, divert their

gaze from the Madonna.

a high-quality picture of

Feast of the Rose Garlands (Left) for your computer or notebook. ‣

St Dominic is clearly the saint whom we see to the left of the Madonna,

since the institution of the rosary is attributed to him. For all the

others, many names have been proposed. However, the identifications are

still uncertain. The Madonna is enthroned in a field, beneath a green

canopy that cherubs hold up with ribbons. Other cherubs on little clouds

hold a crown of precious stones suspended above her head. At her feet

kneel the pope and the emperor, on the left and right, having placed before

themselves a tiara and a crown, respectively. And while the Madonna places

a garland of roses on the head of the emperor, the Blessed Child places an

identical one over the head of the pontifice. St. Dominic, in turn, crowns

a bishop. Behind the pope and the emperor, the patrons are arranged

symmetrically, some of whom, in both parts of the background, divert their

gaze from the Madonna.

In the crowd of believers Durer combined real portraits which he prepared in studies with fictitious ones. In the Feast of the Rose Garlands, Durer created his first single panel altar, though its compositional structure is like a triptych.

Other Bellinian cherubs descend upon them with rose garlands; the setting of the work is typically Venetian. The rigidly pyramidal composition of the painting is not Venetian. This painting has indicated that Durer was one to have been of the first who created such composition.

Feast of the Rose Garlands (1506)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Feast of the Rose Garlands for your computer or notebook. ‣

This panel was painted for an altar for the German community in Venice,

in the church of S. Bartolomeo near the Fondaco dei Tedeschi, the social

and commercial centre of the German colony, where it remained until 1606.

It was then acquired, after many negotiations, for 900 ducats by Emperor

Rudolph II. According to Sandrart (1675), four men were hired to bring the

packaged painting to the emperor's residence in Prague.

a high-quality picture of

Feast of the Rose Garlands for your computer or notebook. ‣

This panel was painted for an altar for the German community in Venice,

in the church of S. Bartolomeo near the Fondaco dei Tedeschi, the social

and commercial centre of the German colony, where it remained until 1606.

It was then acquired, after many negotiations, for 900 ducats by Emperor

Rudolph II. According to Sandrart (1675), four men were hired to bring the

packaged painting to the emperor's residence in Prague.

Stationed elsewhere during the invasion of the Swedish troops, the painting, already very damaged, returned to its place in 1635. It underwent a first restoration in 1662. In 1782, it was sold in an auction for one florin. After having passed through the hands of various collectors, it was acquired by the Czechoslovakian state in 1930.

The painting, severely damaged chiefly in the centre portion, from the head of the Madonna and continuing downward to the bottom, was clumsily restored in the nineteenth century; in this restoration, the upper side portion, left of the canopy and to Saint Dominic's head, was also included. Three copies of the work are known: one - considered the most important and which now belongs to a private collection - is attributed to Hans Rottenhamer, who sojourned in Venice from 1596 to 1606, where he took care of many acquisitions on behalf of Rudolph II; another is in Vienna; and the third, a rather modified version of the original, is in Lyon.

The preparatory work of the panel occupied the artist for a long time, from 7 February until the last half of April in 1506. It consists of twenty-one preparatory drawings, executed chiefly in pen and ink on azure paper, according to the Venetian tradition; others are drawings of various characters, in the dimensions then adopted for the painting. In a letter dated 25 September, addressed to Willibald Pirckheimer, the artist communicates the completion of the work.

It seems that the Confraternity of the Blessed Rosary was officially recognized by the Venetian authorities in 1506, that is, in the year Durer carried out the painting. It is assumed that the painting was ordered by this Confraternity. On the whole, the majority of the figures in the painting have not been identified. The exceptions to this include the self-portrait of the artist; the portrait of Emperor Maximilian I; the one of the architect Hieronymus of Augsburg, engineer of the new Fondaco dei Tedeschi (1505-8) after it was completely destroyed in a fire, and who is recognizable in the far right by the square he holds; and Burckhard from the city Speyer, identified as the fourth figure form the left.

St Dominic is clearly the saint whom we see to the left of the Madonna, since the institution of the rosary is attributed to him. For all the others, many names have been proposed. However, the identifications are still uncertain. The Madonna is enthroned in a field, beneath a green canopy that cherubs hold up with ribbons. Other cherubs on little clouds hold a crown of precious stones suspended above her head. At her feet kneel the pope and the emperor, on the left and right, having placed before themselves a tiara and a crown, respectively. And while the Madonna places a garland of roses on the head of the emperor, the Blessed Child places an identical one over the head of the pontifice. St. Dominic, in turn, crowns a bishop. Behind the pope and the emperor, the patrons are arranged symmetrically, some of whom, in both parts of the background, divert their gaze from the Madonna. Other Bellinian cherubs descend upon them with rose garlands. In the centre of the painting, seated in front of the throne, an angel playing a lute recalls the angels playing at the feet of the enthroned Madonna in Giovanni Bellini's paintings. These details aside, the setting of the work is typically Venetian. The rigidly pyramidal composition of the painting is not Venetian. This painting has indicated that Durer was one to have been of the first who created such composition.

The Feast of the Rose Garlands is undoubtedly the most important work that Durer created during his sojourn in Venice and was the work that ushered in the Renaissance. Durer was obviously aware of this, as his letters and the painting itself demonstrate. The painting shows this in the distinction he gives his self-portrait: in the top right, in front of the typically German landscape passage at the foot of the mountains, with his face framed by long blond hair, donning luxurious clothes - even a precious fur cloak, in spite of the warm season - so as to be noticed among the other characters. He alone has ostentatiously turned his gaze to the spectator. Even the writing on the paper he holds is unusual for Italy. It indicates not only the time of production (five months), but next to his own name is the indication germanus. This detail was to distinguish himself from his Venetian colleagues, who evidently held him in very high regard, since even the doge and the patriarch came to his workshop to admire his work.

Madonna with the Siskin (Detail 3) (1506)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Madonna with the Siskin (Detail 3) for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Virgin, depicted here with flowing, fair hair, is seated before a

red backcloth in a landscape, while two angels hold a garland of roses

over her head. The Child is shown playing with a siskin and holding a

sugar-castor in his right hand. The Madonna's left hand rests on a book,

and with the other she takes a spray of lily of the valley which the young

Saint John is holding out to her.

a high-quality picture of

Madonna with the Siskin (Detail 3) for your computer or notebook. ‣

The Virgin, depicted here with flowing, fair hair, is seated before a

red backcloth in a landscape, while two angels hold a garland of roses

over her head. The Child is shown playing with a siskin and holding a

sugar-castor in his right hand. The Madonna's left hand rests on a book,

and with the other she takes a spray of lily of the valley which the young

Saint John is holding out to her.

On a wooden bench in the foreground lies a piece of paper bearing the painter's signature in Latin : 'Albertus durer germanus faciebat post virginis partum 1506'. That Durer should here describe himself specifically as German is not surprising when one takes into account his admiration for the Italian artists. He has included quite a few Venetian touches in this picture and was obviously proud of his achievement. The type of half-length figure he has adopted for the Madonna is modelled on southern paintings and the characteristic blue and red colour-scheme is adopted from Giovanni Bellini, whom Durer, as he wrote in a letter to Nuremberg at the time, regarded as 'the best of all painters'. The flying cherubim, bodyless angels, were also derived from the Italian Renaissance masters. Saint John, presenting the flowers, is closely akin to the small figure in Titian's Madonna of the Cherries in the Vienna Gallery, which was not painted until the second decade of the century. Here the Venetian master showed his respect for the German artist.

Quite a lot is known about Durer's visit to Venice in 1506. He received a major commission from the German merchants at the Fondaco dei Tedeschi, who later also commissioned works from Giorgione and Titian; Durer's work, the Festival of the Rosary, now in Prague, proved a difficult task which kept him busy and preoccupied for a long time, as he himself admitted; as a result he lost other commissions. He had only the last quarter of the year 1506 in which to complete the Madonna with the Siskin, for the following spring he returned to Nuremberg; thus it became an Italian Christmas picture, as the inscription 'after the confinement of the Virgin' expressly states. There are four extant studies for this painting, in which the Child, the cherubim and a piece of drapery are portrayed (Bremen, Paris, Vienna). These sketches also show how closely the creation of the Berlin panel was linked with the Festival of the Rosary.

Painted for an unknown patron, the work was probably in the palace of Rudolf II in Prague, assuming that Carel van Mander's description of 1618 - 'a Madonna, over whom two angels hold a garland of roses, with which to crown her' - refers to this painting. How it came from Italy to Prague is as much a mystery as its subsequent movements. In the 1860s the panel was rediscovered in Scotland; it was in Newbattle Abbey near Edinburgh in 1892 when it was acquired for the Berlin Gallery from the Marquess of Lothian.

Madonna with the Siskin (1506)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Madonna with the Siskin for your computer or notebook. ‣

In the second half of the sixteenth century, this painting was in

Nuremberg; in 1600, it was part of the collection of Rudolph II. In the

1860s, it reappeared and became the property of the marquis of Lothian of

Edinburgh, from whom the Berlin museum acquired it in 1893.

a high-quality picture of

Madonna with the Siskin for your computer or notebook. ‣

In the second half of the sixteenth century, this painting was in

Nuremberg; in 1600, it was part of the collection of Rudolph II. In the

1860s, it reappeared and became the property of the marquis of Lothian of

Edinburgh, from whom the Berlin museum acquired it in 1893.

In a letter of 23 September 1506 from Venice addressed to Willibald Pirckheimer, in which Durer writes that he has completed the Feast of the Rose Garlands (National Gallery, Prague), he also speaks of having just finished another painting. It would most likely be the Madonna with the Siskin, which the artist brought back to Nuremberg with him. It is astonishing that Durer does not mention any patrons for this large painting, full of iconographical references. He created it simply by drawing on his own culture and experience.

The work is conceived following the dictates of Venetian painting: a monumental Madonna, with the red gown covered by an azure cloak, who sits enthroned before a curtain that is also red, in a landscape pervaded by an especially clear light. A Florentine trademark is represented in the presence of Saint John, even if this detail was also rather common in the Venetian painting by this time. The Madonna's rapt gaze is directed slightly off to the side, while her right hand rests on the Old Testament, in which is prophesied the birth of the new king. She almost unconsciously accepts a lily of the valley (convallaris majalis) from Saint John with her other hand. It is the flower symbolic of the Immaculate Conception and the Incarnation of Christ. The small saint, however, does not look at her; his gaze is directed to Jesus, whose divine nature Saint John is the first to recognize.

The infant Jesus is seated in his mother's lap on a rich red cushion. With his right hand, he elegantly lifts a sort of soother - a tiny pouch, apparently filled with poppy seeds, on which babies would suck and be calmed. His left hand, which holds the edge of his little shirt, probably just unfastened (see the open clasp), comes toward his face. In the preparatory drawing, Durer had represented him with a more solemn expression, while he raised the cross staff; but perhaps in changing the staff, the symbol of the Passion, with the poppy-seed soother - poppy seeds symbolic of sleep and death, if this is actually what it contains - the artist wanted to preserve the childlike manner of the infant Jesus, without altering the symbolism.

The siskin - in the place of the goldfinch - perched on his arm points his beak toward his head, where one day the crown of thorns will be; the child smiles affectionately at Saint John below him, to whom a little angel, with a meaningful gaze, is holding the cross staff out to him, though the saint and child do not take notice.

To the ruins represented in perspective on the left corresponds a tree in bloom growing from a fallen trunk on the right. The former is a symbol of the fall of the Old Covenant, or perhaps an image of the ruins of David's palace, where, according to the legend, the nativity stable stood. The latter is a sign of life and of the New Covenant.

Two cherubs crown the Madonna with a garland of vine shoots of roses, in which are woven a white rose, symbol of her joy, and two red roses, symbol of her sufferings.

Durer's main accomplishment in this painting is in the perfect combination of form and content. Each of the characters expresses his or her own emotion, yet everyone together is composed in a convincing, unified story, the symbols included. Unfortunately, the poor state of preservation greatly disturbs the impression of overall harmony that characterizes the panel.

Adam (1507)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Adam for your computer or notebook. ‣

The subject of Adam and Eve offered Durer the opportunity to depict the

ideal human figure. Painted in Nuremberg soon after his return from

Venice, the panels were influenced by Italian art. Durer's colouring is

muted, and he models the bodies with the help of light and shadow, making

the figures emerge from the dark background. Adam and Eve are noticeably

slimmer than in his engraving of three years earlier.

a high-quality picture of

Adam for your computer or notebook. ‣

The subject of Adam and Eve offered Durer the opportunity to depict the

ideal human figure. Painted in Nuremberg soon after his return from

Venice, the panels were influenced by Italian art. Durer's colouring is

muted, and he models the bodies with the help of light and shadow, making

the figures emerge from the dark background. Adam and Eve are noticeably

slimmer than in his engraving of three years earlier.

Following his copper engraving dating from 1504, Durer produced another painted version of the theme of the first human couple three years later. The two pictures of Adam and Eve (also in the Prado, Madrid) were created by Durer after returning from his second journey to Italy. In spite of the nearly identical size of the two pictures they were intended to be separate paintings. This is corroborated by the fact that both paintings are signed although in a different way: on the lower right corner in present picture, on the small tablet hanging on the apple-tree branch held by Eve in the painting of Eve. However, the two paintings are related to each other in their composition and the movement of the figures' bodies. Adam, who is holding a branch from the Tree of Knowledge in front of himself, is turning yearningly towards Eve in the other panel. Like Eve, he is depicted in motion, walking with his hair blowing back.

The primary aim of the artist in both cases was not depicting a Biblical story but creating two nude figures. These are the first German paintings representing life size nude figures.

Eve (1507)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Eve for your computer or notebook. ‣

Durer's Adam and Eve represent the earliest known life-size nudes in

Northern art. Eve, whose skin is whiter than Adam's, is next to the Tree

of Knowledge, standing in a curious position with one foot behind the

other. Her right hand rests on a bough and with her left hand she accepts

the ripe apple offered by the coiled serpent. On a tablet is the

inscription: 'Albrecht Durer, Upper German, made this 1507 years after the

Virgin's offspring.' Adam inclines his head towards Eve and stretches out

the fingers of his right hand on the other side, creating a sense of

balance.

a high-quality picture of

Eve for your computer or notebook. ‣

Durer's Adam and Eve represent the earliest known life-size nudes in

Northern art. Eve, whose skin is whiter than Adam's, is next to the Tree

of Knowledge, standing in a curious position with one foot behind the

other. Her right hand rests on a bough and with her left hand she accepts

the ripe apple offered by the coiled serpent. On a tablet is the

inscription: 'Albrecht Durer, Upper German, made this 1507 years after the

Virgin's offspring.' Adam inclines his head towards Eve and stretches out

the fingers of his right hand on the other side, creating a sense of

balance.

Like the depiction of Adam (also in the Prado, Madrid), that of Eve should also be considered in the context of the studies relating to the ideal proportions of the human body which Durer had been making since his first Italian journey in 1496. The plastic values of the painting are toned down compared to those in the copper engraving, and the interior detail is gentler. Eve is gazing seductively across at Adam. In her left hand she is receiving the apple from the serpent, and in her right she is holding a branch from the Tree of Knowledge from which hangs a cartellino, a small inscribed plaque with the signature and phrase "Albertus Durer alemanus faciebat post virginis partum 1507" (The German Albrecht Durer made this after the Virgin gave birth 1507).

The Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand (Detail 2) (1508)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand (Detail 2) for your computer or notebook. ‣

This picture was intended for the chamber of relics in the Wittenberg

castle chapel, and was created as a result of the Saxonian Elector

Frederick the Wise's worship of relics. In several horizontal picture

fields, arranged parallel to each other, Durer depicted the account in the

Legenda aurea of how the Christian company of soldiers with Bishop

Achatius, which had been converted to the Christian faith by a miracle,

was executed on Mount Ararat. The Roman rulers Hadrian and Antoninus

commissioned seven Oriental princes to carry out the execution, and they

stand out here in their splendid turbans and robes.

a high-quality picture of

The Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand (Detail 2) for your computer or notebook. ‣

This picture was intended for the chamber of relics in the Wittenberg

castle chapel, and was created as a result of the Saxonian Elector

Frederick the Wise's worship of relics. In several horizontal picture

fields, arranged parallel to each other, Durer depicted the account in the

Legenda aurea of how the Christian company of soldiers with Bishop

Achatius, which had been converted to the Christian faith by a miracle,

was executed on Mount Ararat. The Roman rulers Hadrian and Antoninus

commissioned seven Oriental princes to carry out the execution, and they

stand out here in their splendid turbans and robes.

The representation of the violence of the torturers and the various positions of their victims, on their knees and lying on the ground, demonstrates the wide knowledge Durer had acquired about the human form and laws of perspective. A refined psychological sensibility and pictorial mastery characterize almost all the figures of this tragic scene: for example, the almost cinematographic sequence of the people who are made to fall from the cliff in the top left.

The Martydom of the Ten Thousand (1508)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

The Martydom of the Ten Thousand for your computer or notebook. ‣

The altarpiece depicts the legend of the ten thousand Christians who

were martyred on Mount Ararat, in a massacre perpetrated by the Persian

King Saporat on the command of the Roman Emperors Hadrian and Antonius.

Durer had depicted this massacre a decade earlier in a woodcut. The

painting was commissioned by Frederick the Wise, who owned relics from the

massacre, and it was placed in the relic chamber of his palace church in

Wittenberg. Although Durer had never before tackled a painting with so

many figures, he succeeded in integrating them into a flowing composition

using vibrant colour.

a high-quality picture of

The Martydom of the Ten Thousand for your computer or notebook. ‣

The altarpiece depicts the legend of the ten thousand Christians who

were martyred on Mount Ararat, in a massacre perpetrated by the Persian

King Saporat on the command of the Roman Emperors Hadrian and Antonius.

Durer had depicted this massacre a decade earlier in a woodcut. The

painting was commissioned by Frederick the Wise, who owned relics from the

massacre, and it was placed in the relic chamber of his palace church in

Wittenberg. Although Durer had never before tackled a painting with so

many figures, he succeeded in integrating them into a flowing composition

using vibrant colour.

Durer's gruesome scene depicts scores of Christians meeting a violent death in a rocky landscape, providing a veritable compendium of tortures and killings. The oriental potentate in the blue cloak and turban who is directing the action in the lower right corner of the picture, would in Durer's time have been perceived as a reference to the threat of Turkish invasion, because of the seizure of Constantinople in 1453. In the centre of the painting is the rather incongruous figure of the artist, holding a staff with the inscription: 'This work was done in the year 1508 by Albrecht Durer, German.' The man walking with him through this scene of carnage is probably the scholar Konrad Celtis, a friend of Durer's who had died just before the painting was completed.

Heller Altar (Detail) (1509)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Heller Altar (Detail) for your computer or notebook. ‣

This altarpiece was commissioned by Jakob Heller (1460-1522), a wealthy

merchant, member of the town council, and mayor of Frankfurt, either