Albrecht Durer

Albrecht Durer, a German painter and printmaker.

Durer is generally regarded as the greatest Northern Renaissance artist. His famous paintings have been the subject of

extensive analysis and interpretation. His watercolours

mark him as one of the first European landscape artists, while his

ambitious woodcuts revolutionized the potential of that medium.

Durer's introduction of classical motifs into Northern art, through

his knowledge of Italian artists and German humanists, have secured

his reputation as one of the most important figures of the Northern

Renaissance. This is reinforced by his theoretical works which involve

principles of mathematics, perspective and ideal proportions. The

quality and wide range of his works and themes, both in terms

of content and formal aspects, are astonishing. Though his paintings

were normally produced as the result of a commission - his two main

areas of focus were portrait painting and the creation of altar pieces

and devotional pictures - Durer enriched them with unusual pictorial

solutions and adapted them to new functions.

After his death, Durer remained one of the most highly regarded of

artists for centuries, representing the process of transition from the

late Middle Ages to the Renaissance in Germany.

Albrecht Durer, a German painter and printmaker.

Durer is generally regarded as the greatest Northern Renaissance artist. His famous paintings have been the subject of

extensive analysis and interpretation. His watercolours

mark him as one of the first European landscape artists, while his

ambitious woodcuts revolutionized the potential of that medium.

Durer's introduction of classical motifs into Northern art, through

his knowledge of Italian artists and German humanists, have secured

his reputation as one of the most important figures of the Northern

Renaissance. This is reinforced by his theoretical works which involve

principles of mathematics, perspective and ideal proportions. The

quality and wide range of his works and themes, both in terms

of content and formal aspects, are astonishing. Though his paintings

were normally produced as the result of a commission - his two main

areas of focus were portrait painting and the creation of altar pieces

and devotional pictures - Durer enriched them with unusual pictorial

solutions and adapted them to new functions.

After his death, Durer remained one of the most highly regarded of

artists for centuries, representing the process of transition from the

late Middle Ages to the Renaissance in Germany.

Portraits by Durer

- Portrait of Barbara Durer (1490)

- Portrait of Albrecht Durer the Elder (1490)

- Self-Portrait at 22 (1493)

- Portrait of Elector Frederick the Wise of Saxony (1496)

- Portrait of Durer's Father at 70 (1497)

- Portrait of a Young Furleger with Her Hair Done Up (1497)

- Portrait of a Young Furleger with Loose Hair (1497)

- Portrait of a Man (1498)

- Self-Portrait at 26 (1498)

- Felicitas Tucher, nee Rieter (1499)

- Hans Tucher (1499)

- Portrait of Elsbeth Tucher (1499)

- Portrait of Oswolt Krel (1499)

- Portrait of St. Sebastian with an Arrow (1499)

- Self-Portrait in a Fur-Collared Robe (1500)

- Portrait of Young Man (1500)

- Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman (1505)

- Portrait of Burkard von Speyer (1506)

- Portrait of a Venetian Woman (1507)

- Portrait of a Young Girl (1507)

- Portrait of a Young Man (1506)

- Emperor Charlemagne (1512)

- Emperor Sigismund (1512)

- Portrait of Michael Wolgemut (1516)

- Portrait of a Cleric (1516)

- Portrait of Emperor Maximilian I (1519)

- Jakob Fugger, the Wealthy (1520)

- Portrait of Bernhard von Reesen (1521)

- Portrait of a Man with Baret and Scroll (1521)

- Portrait of Hieronymus Holzchuher (1526)

- Portrait of Jakob Muffel (1526)

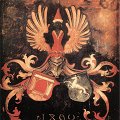

- Alliance Coat of Arms of the Durer and Holper Families (1490)

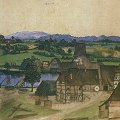

- Wire-Drawing Mill (1494)

- The Courtyard of the Castle in Innsbruck with Clouds (1494)

- The Courtyard of the Castle in Innsbruck without Clouds (1494)

- Pond in the Woods (1496)

- Young Hare (1502)

- The Large Turf (1503)

Portrait of Barbara Durer (1490)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Barbara Durer for your computer or notebook. ‣

Shortly before his departure as a journeyman, Durer painted the double

portrait of his parents, his first painted portraits. The portrait of his

mother acted as the counterpart to the portrait of his father, and is

related to the latter in terms of line of sight and body posture. The

portraits are closely matched to each other in terms of composition. The

mother, with a white bonnet, appears as a married woman in a dark red

garment. While the latter is recorded in a summary fashion, her

physiognomy is depicted meticulously. His mother is holding a rosary in her

hand as an expression of her piety, and this gesture is another way in

which she is related to the depiction of his father.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Barbara Durer for your computer or notebook. ‣

Shortly before his departure as a journeyman, Durer painted the double

portrait of his parents, his first painted portraits. The portrait of his

mother acted as the counterpart to the portrait of his father, and is

related to the latter in terms of line of sight and body posture. The

portraits are closely matched to each other in terms of composition. The

mother, with a white bonnet, appears as a married woman in a dark red

garment. While the latter is recorded in a summary fashion, her

physiognomy is depicted meticulously. His mother is holding a rosary in her

hand as an expression of her piety, and this gesture is another way in

which she is related to the depiction of his father.

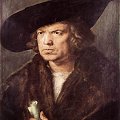

Portrait of Albrecht Durer the Elder (1490)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Albrecht Durer the Elder for your computer or notebook. ‣

Durer's earliest surviving oil painting, done just after he finished

his apprenticeship, is a portrait of his father, the goldsmith Albrecht the

Elder (1427-1502). Dated 1490, it was painted early in the year, before

Durer left Nuremberg on his journeyman travels in April. Albrecht the

Elder, then probably aged 62 (or 63 if he was born at the beginning of

1427), is depicted from the waist up, wearing a black hat and brown. cape

lined with black fur. He holds a rosary. Durer later wrote that his father

lived an honourable, Christian life, was a man patient of spirit, mild and

peaceable to all, and very thankful towards God'.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Albrecht Durer the Elder for your computer or notebook. ‣

Durer's earliest surviving oil painting, done just after he finished

his apprenticeship, is a portrait of his father, the goldsmith Albrecht the

Elder (1427-1502). Dated 1490, it was painted early in the year, before

Durer left Nuremberg on his journeyman travels in April. Albrecht the

Elder, then probably aged 62 (or 63 if he was born at the beginning of

1427), is depicted from the waist up, wearing a black hat and brown. cape

lined with black fur. He holds a rosary. Durer later wrote that his father

lived an honourable, Christian life, was a man patient of spirit, mild and

peaceable to all, and very thankful towards God'.

On the reverse of this portrait are the coats of arms of Albrecht the Elder and those of his wife Barbara Holper. The family name 'Durer' originated from the name of the birthplace of Albrecht the Elder's father, since the village of Ajto where he came from means 'door' in Hungarian and this was translated into German as 'Ture' or 'Dure'. The Durer coat of arms therefore bears an emblematic, open double-door. The portrait of Albrecht the Elder may well have been the right wing of a diptych, with the other panel portraying his wife. A portrait believed to be of Barbara Holper, still in Nuremberg and attributed to Durer, could well be the other half of the diptych, although it may be an early copy of a lost original.

Self-Portrait at 22 (1493)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Self-Portrait at 22 for your computer or notebook. ‣

This is Durer's first painted self portrait, dated 1493. It is the

earliest known self portrait in European art produced as an independent

painting (although earlier artists had sometimes portrayed themselves

among figures in an altarpiece or fresco). A sketched self portrait, dated

1493 on the reverse, could well have been an early study for the oil

painting. Durer completed the oil painting towards the end of his travels

as a journeyman, almost certainly in Strasbourg. It was originally on

vellum, which would have made it relatively simple to transport, and this

suggests that it might well have been sent back to Nuremberg.

a high-quality picture of

Self-Portrait at 22 for your computer or notebook. ‣

This is Durer's first painted self portrait, dated 1493. It is the

earliest known self portrait in European art produced as an independent

painting (although earlier artists had sometimes portrayed themselves

among figures in an altarpiece or fresco). A sketched self portrait, dated

1493 on the reverse, could well have been an early study for the oil

painting. Durer completed the oil painting towards the end of his travels

as a journeyman, almost certainly in Strasbourg. It was originally on

vellum, which would have made it relatively simple to transport, and this

suggests that it might well have been sent back to Nuremberg.

Durer inscribed at the top of the self portrait: "Things with me fare as ordained from above", a sign of his faith in God. The artist's youthful features are framed by his lanky, ginger hair, which is topped by a red tasselled cap. Beneath his grey cloak, fringed with red, he wears an elegant pleated shirt with pink ribbons. His strong nose, heart-shaped upper lip and long neck are emphasized in the painting. Using a mirror, Durer obviously found it difficult to paint his hands and eyes, the two features which are always a challenge in a self portrait.

In his rough hands, Durer holds a sprig of sea holly, a thistle-like plant. Its German name means "man's fidelity" and this, together with the fact that the plant was sometimes regarded as an aphrodisiac, has led to speculation that the self portrait was intended as a gift for his fiancie. While Durer was away, his father had arranged for Agnes Frey to become his wife and they eventually married on 7 July 1494, two months after his return to Nuremberg. However, it is just as likely that the self portrait was a gift for his parents, whom he had not seen for nearly four years. One can imagine the surprise and pleasure they must have felt to receive this picture after their son's long absence. It would have been a reminder of his handsome features and further evidence of his blossoming talent.

Portrait of Elector Frederick the Wise of Saxony (1496)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Elector Frederick the Wise of Saxony for your computer or notebook. ‣

Frederick III (1463-1525), known as Frederick the Wise, had became

Elector of Saxony in 1486 and was one of the princes entitled to select

the Holy Roman Emperor. He later became Durer's first major patron. This

portrait was probably done when Frederick the Wise visited Nuremberg from

14-18 April 1496. Durer used quick-drying tempera paint, rather than oil

paint, and this may have been so that the picture could be taken away.

Frederick the Wise, then 33, is depicted from the waist up, elegantly

dressed and set against a light-green background. His folded arms rest on

a ledge and in his left hand he holds a small scroll. The monarch's slight

frown is probably intended to convey fortitude. The most striking aspect

of the portrait are Frederick's piercing eyes, staring straight at the

viewer.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Elector Frederick the Wise of Saxony for your computer or notebook. ‣

Frederick III (1463-1525), known as Frederick the Wise, had became

Elector of Saxony in 1486 and was one of the princes entitled to select

the Holy Roman Emperor. He later became Durer's first major patron. This

portrait was probably done when Frederick the Wise visited Nuremberg from

14-18 April 1496. Durer used quick-drying tempera paint, rather than oil

paint, and this may have been so that the picture could be taken away.

Frederick the Wise, then 33, is depicted from the waist up, elegantly

dressed and set against a light-green background. His folded arms rest on

a ledge and in his left hand he holds a small scroll. The monarch's slight

frown is probably intended to convey fortitude. The most striking aspect

of the portrait are Frederick's piercing eyes, staring straight at the

viewer.

Frederick the Wise must have been pleased with this portrait as Durer was then commissioned to paint a series of important altarpieces for the church at the Elector's palace in Wittenberg. Durer sketched Frederick the Wise 27 years later as an elderly statesman and the following year the drawing was used for an engraving.

Portrait of Durer's Father at 70 (1497)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Durer's Father at 70 for your computer or notebook. ‣

The portrait is inscribed '1497 Albrecht Durer the Elder at age 70'.

Durer's father appears considerably older than in the portrait of seven

years earlier. His lips are thinner, his face more heavily lined with

wrinkles and his narrow eyes have a wearier appearance. Yet Albrecht the

Elder has retained his wisdom and dignity. After his death, Durer wrote

that his father passed his life in great toil and stern, hard labour... He

underwent manifold afflictions, trials and adversities.' Albrecht the

Elder died five years after this portrait was painted, at the age of 75.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Durer's Father at 70 for your computer or notebook. ‣

The portrait is inscribed '1497 Albrecht Durer the Elder at age 70'.

Durer's father appears considerably older than in the portrait of seven

years earlier. His lips are thinner, his face more heavily lined with

wrinkles and his narrow eyes have a wearier appearance. Yet Albrecht the

Elder has retained his wisdom and dignity. After his death, Durer wrote

that his father passed his life in great toil and stern, hard labour... He

underwent manifold afflictions, trials and adversities.' Albrecht the

Elder died five years after this portrait was painted, at the age of 75.

The condition of this painting is poor, particularly in the background and the cloak, and in the past many scholars believed that it was a copy of a lost original. However, since it was cleaned in 1955, there has been more support for the view that this is indeed the original. Fortunately the face is the part of the picture which remains in the best condition.

This portrait may originally have been displayed with Durer's self-portrait of the following year, either hung in the same room in the family home or even linked as a diptych. Although Durer and his father are wearing very different clothing and the backgrounds do not match, the two portraits are almost the same size and the half length poses are similar. The pictures were apparently kept together as a pair, since they were presented by the city of Nuremberg to the Earl of Arundel in 1636 as a gift for Charles I of England. Both paintings were sold in 1650 by Cromwell. The portrait of Albrecht Durer the Elder stayed in Britain and was eventually bought by the National Gallery in 1904.

Portrait of a Young Furleger with Her Hair Done Up (1497)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of a Young Furleger with Her Hair Done Up for your computer or notebook. ‣

This portrait, together with the Portrait of a Young Furleger with

Loose Hai, forms part of a diptych. When the portraits were still together,

they passed on from Carl von Waagen to other owners, until it alone was

finally acquired by the museums of Berlin in 1977. The various

restorations have partially or entirely destroyed areas of the landscape

and the inscription on the card at the top; the same holds true for the

small statue of the prophet, inserted in the window post, which, from the

side, looked toward the other portrait and in whose book Durer had written

his monogram, as Wenzel Hollar's engraving shows. At one time, the two

portraits were considered to be two representations of the same person,

namely, Katharina Furleger. The series of letters on the trim of the

blouse also seemed to point to this; however, they are probably the

initials of a motto. Today, it is generally believed that they are

portraits of two younger sisters of the Furleger family. The portrait,

along with its companion-piece, acts as part of a fairly uncommon diptych;

it is the representation of the two Furleger sisters of Nuremberg.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of a Young Furleger with Her Hair Done Up for your computer or notebook. ‣

This portrait, together with the Portrait of a Young Furleger with

Loose Hai, forms part of a diptych. When the portraits were still together,

they passed on from Carl von Waagen to other owners, until it alone was

finally acquired by the museums of Berlin in 1977. The various

restorations have partially or entirely destroyed areas of the landscape

and the inscription on the card at the top; the same holds true for the

small statue of the prophet, inserted in the window post, which, from the

side, looked toward the other portrait and in whose book Durer had written

his monogram, as Wenzel Hollar's engraving shows. At one time, the two

portraits were considered to be two representations of the same person,

namely, Katharina Furleger. The series of letters on the trim of the

blouse also seemed to point to this; however, they are probably the

initials of a motto. Today, it is generally believed that they are

portraits of two younger sisters of the Furleger family. The portrait,

along with its companion-piece, acts as part of a fairly uncommon diptych;

it is the representation of the two Furleger sisters of Nuremberg.

In contrast to the other young woman, depicted with loose hair, this one - an eighteen-year-old, according to the inscription - wears her hair in large braids wrapped around her head, a sign that she opted for marriage. Her defiant gaze is also proof of this. Similarly allude the sprigs of sea holly (Eryngium campestre) and Southernwood (Artemisia abrotanum), symbols of conjugal fidelity and eroticism, which she holds in her hand. Note that one of the portraits has a neutral background, while the other has a window with a landscape scene. One interpretation could be that one of the young women renounces the world, while the other welcomes it openly. In both figures, Durer reveals pathologic symptoms: the young woman with the loose hair has goiter, and the two of them show signs of arthritis in their hands.

Portrait of a Young Furleger with Loose Hair (1497)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of a Young Furleger with Loose Hair for your computer or notebook. ‣

This portrait, together with the Portrait of a Young Furleger with Her

Hair Done Up, forms part of a rather uncommon diptych. The coats of arms,

added shortly after and placed on the external side beside the portraits,

were those of the same family, even though the coats of arms are

different: one has a cross between two fish, the other an upside-down

lily.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of a Young Furleger with Loose Hair for your computer or notebook. ‣

This portrait, together with the Portrait of a Young Furleger with Her

Hair Done Up, forms part of a rather uncommon diptych. The coats of arms,

added shortly after and placed on the external side beside the portraits,

were those of the same family, even though the coats of arms are

different: one has a cross between two fish, the other an upside-down

lily.

The emperor Sigismund had authorized the families of ecclesiastic members to add a cross to their own coats of arms. For this reason, it was deduced that the young woman portrayed with loose hair, the coral bracelet, the hands joined in prayer, and her head bowed down had devoted herself to the cloistered life. The Latin inscription added to the engraving Wenzel Hollar modeled on this painting, also recommended following in the path of Christ.

The very fine brushstrokes of this exquisite painting and the sharp distinction between the areas in light and those in shadow give the face a sense of plasticity, endowing it with a particularly vivid expression. Scholars demonstrated that the two portraits truly formed a pair and that they were acquired together in 1636 in Nuremberg by the count of Arundel, whose engraver, Wenzel Hollar, made two engravings modeled from them. It should be noted that the young woman with the loose hair also rests her arms on a window sill.

In 1673, the portraits were acquired, together as always, by the bishop of Olmutz, from whom they later went on to Carl von Waagen, of Munich. Afterward, the two portraits were separated.

Portrait of a Man (1498)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of a Man for your computer or notebook. ‣

The contrast between the internal strength that emanates from his face,

and the wisdom and foresight in his eyes, on the one hand - and the messy

and wild hair, on the other, effectively demonstrates the breadth of

Durer's skills as a painter, even if the completely distorted perspective

of the left shoulder remains inexplicable.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of a Man for your computer or notebook. ‣

The contrast between the internal strength that emanates from his face,

and the wisdom and foresight in his eyes, on the one hand - and the messy

and wild hair, on the other, effectively demonstrates the breadth of

Durer's skills as a painter, even if the completely distorted perspective

of the left shoulder remains inexplicable.

Heinz Kisters acquired this painting in 1952 from the antique market in London. The state of preservation, following the removal of one layer of a painting that had been painted over it, appears relatively good. The painting has been included among the Durer's original works.

Self-Portrait at 26 (1498)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Self-Portrait at 26 for your computer or notebook. ‣

This self portrait is dated 1498 and inscribed: "I have thus painted

myself. I was 26 years old. Albrecht Durer." Since the artist turned 27 on

the 21 May, the picture must date from the beginning of the year. The

artist's pose is self confident, showing him standing upright and turning

slightly to lean his right arm on a ledge. Durer's figure fills the

picture, with his hat almost touching the top. His face and neck glow from

the light streaming into the room and his long curly hair is painstakingly

depicted. Unlike his earlier self portrait, he now has a proper beard,

which was then unusual among young men. Nine years later Durer wrote an

ironic poem in which he described himself as 'the painter with the hairy

beard'.

a high-quality picture of

Self-Portrait at 26 for your computer or notebook. ‣

This self portrait is dated 1498 and inscribed: "I have thus painted

myself. I was 26 years old. Albrecht Durer." Since the artist turned 27 on

the 21 May, the picture must date from the beginning of the year. The

artist's pose is self confident, showing him standing upright and turning

slightly to lean his right arm on a ledge. Durer's figure fills the

picture, with his hat almost touching the top. His face and neck glow from

the light streaming into the room and his long curly hair is painstakingly

depicted. Unlike his earlier self portrait, he now has a proper beard,

which was then unusual among young men. Nine years later Durer wrote an

ironic poem in which he described himself as 'the painter with the hairy

beard'.

The artist's clothing is flamboyant. His elegant jacket is edged with black and beneath this he wears a white, pleated shirt, embroidered along the neckline. His jaunty hat is striped, to match the jacket. Over his left shoulder hangs a light-brown cloak, tied around his neck with a twisted cord. He wears fine kid gloves.

Inside the room is a tall archway, partly framing Durer's head, and to the right a window opens out onto an exquisite landscape. Green fields give way to a tree-ringed lake and beyond are snow-capped mountains, probably a reminder of Durer's journey over the Alps three years earlier. Depicting a distant landscape, viewed through a window, was a device borrowed from Netherlandish portraiture.

The Germans still tended to consider the artist as a craftsman, as had been the conventional view during the Middle Ages. This was bitterly unacceptable to Durer, whose second Self-Portrait (out of three) shows him as slender and aristocratic, a haughty and foppish youth, ringletted and impassive. His stylish and expensive costume indicates, like the dramatic mountain view through the window (implying wider horizons), that he considers himself no mere limited provincial. What Durer insists on above all else is his dignity, and this was a quality that he allowed to others too.

This picture was acquired by Charles I of England and later bought by Philip IV of Spain.

Felicitas Tucher, nee Rieter (1499)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Felicitas Tucher, nee Rieter for your computer or notebook. ‣

It was commissioned in the same year as the diptych of Nicolas and

Elsbeth Tucher (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Kassel). They had

approximately the same composition because Wolgemut, Durer's master, had

already done portraits of the members of the Tucher family years before.

Even the setting of the portraits is very similar. The presence of an

embroidered curtain in the background, the almost identical landscape

passage seen through the windows, and lastly, the windowsill set equal

spatial limits to the portraits. The foreshortenings of the landscape

passage are imaginative and mannered, showing roads, lakes, and mountains.

On the road, in the landscape behind the man's portrait, one discerns a

wayfarer; on the path, in the woman's portrait, a man on horseback. The

same clouds are seen in the clear sky behind the man, as in the wife's

portrait, and in Elsbeth Tucher's.

a high-quality picture of

Felicitas Tucher, nee Rieter for your computer or notebook. ‣

It was commissioned in the same year as the diptych of Nicolas and

Elsbeth Tucher (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Kassel). They had

approximately the same composition because Wolgemut, Durer's master, had

already done portraits of the members of the Tucher family years before.

Even the setting of the portraits is very similar. The presence of an

embroidered curtain in the background, the almost identical landscape

passage seen through the windows, and lastly, the windowsill set equal

spatial limits to the portraits. The foreshortenings of the landscape

passage are imaginative and mannered, showing roads, lakes, and mountains.

On the road, in the landscape behind the man's portrait, one discerns a

wayfarer; on the path, in the woman's portrait, a man on horseback. The

same clouds are seen in the clear sky behind the man, as in the wife's

portrait, and in Elsbeth Tucher's.

Felicitas holds a carnation, with a bud and a flower. Her plump face is turned to the left, but her gaze, with slightly melancholic eyes, looks to the right. Like her sister-in-law, she wears a gold chain around her neck, and the waistcoat, according to custom, is held by a buckle, which is engraved with the initials of her consort, H. T.

Hans Tucher (1499)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Hans Tucher for your computer or notebook. ‣

It was commissioned in the same year as the diptych of Nicolas and

Elsbeth Tucher (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Kassel). They had

approximately the same composition because Wolgemut, Durer's master, had

already done portraits of the members of the Tucher family years before.

Even the setting of the portraits is very similar. The presence of an

embroidered curtain in the background, the almost identical landscape

passage seen through the windows, and lastly, the windowsill set equal

spatial limits to the portraits. The foreshortenings of the landscape

passage are imaginative and mannered, showing roads, lakes, and mountains.

On the road, in the landscape behind the man's portrait, one discerns a

wayfarer; on the path, in the woman's portrait, a man on horseback. The

same clouds are seen in the clear sky behind the man, as in the wife's

portrait, and in Elsbeth Tucher's.

a high-quality picture of

Hans Tucher for your computer or notebook. ‣

It was commissioned in the same year as the diptych of Nicolas and

Elsbeth Tucher (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Kassel). They had

approximately the same composition because Wolgemut, Durer's master, had

already done portraits of the members of the Tucher family years before.

Even the setting of the portraits is very similar. The presence of an

embroidered curtain in the background, the almost identical landscape

passage seen through the windows, and lastly, the windowsill set equal

spatial limits to the portraits. The foreshortenings of the landscape

passage are imaginative and mannered, showing roads, lakes, and mountains.

On the road, in the landscape behind the man's portrait, one discerns a

wayfarer; on the path, in the woman's portrait, a man on horseback. The

same clouds are seen in the clear sky behind the man, as in the wife's

portrait, and in Elsbeth Tucher's.

Hans Tucher, a descendant of an old Nuremberg family and an important member of the city council, is depicted in lavish clothes, with a fur collar, a symbol of his high-ranking position. The head, portrayed in a more elevated position than that of his consort, is framed by soft and wavy hair. The eyes, which have slightly different size, have an open gaze, the eyelids are somewhat lowered, the nose is long and sharp, the lips thin: the result is a proud but winning look, which is also emphasized by the points of the beret folded to the back and front. Besides the ring he wears on his thumb, he holds - like Elsbeth Tucher in her portrait - another ring, gold, in his hand as evidence of his marriage, contracted in 1482 with Felicitas. She, in turn, holds a carnation, with a bud and a flower. Her plump face is turned to the left, but her gaze, with slightly melancholic eyes, looks to the right. Like her sister-in-law, she wears a gold chain around her neck, and the waistcoat, according to custom, is held by a buckle, which is engraved with the initials of her consort, H. T.

The combined coat of arms of Tucher-Rieter is depicted on the verso of the Hans Tucher portrait, which became the anterior side of the closed diptych.

Portrait of Elsbeth Tucher (1499)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Elsbeth Tucher for your computer or notebook. ‣

Elsbeth Tucher (nie Pusch) is portrayed against an ornate brocade

hanging. At the top of the panel is the inscription, 'Elsbeth Niclas

Tucher at 26 years 1499'. This is the right wing of a diptych, but the left

wing portraying her husband Niclas is missing. Elsbeth holds her wedding

ring and the clasp of her blouse is formed with the initials NT,

presumably a gift from her husband. The initials WW worked into her blouse

and the mysterious letters MHIMNSK on the band over her voluminous

headscarf have so far defied interpretation. Just visible on her shoulders

is a gold necklace, evidence of her social standing. Above the parapet on

the left of the panel is a landscape, with a wood-fringed lake leading to

distant mountains, set beneath a stormy sky.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Elsbeth Tucher for your computer or notebook. ‣

Elsbeth Tucher (nie Pusch) is portrayed against an ornate brocade

hanging. At the top of the panel is the inscription, 'Elsbeth Niclas

Tucher at 26 years 1499'. This is the right wing of a diptych, but the left

wing portraying her husband Niclas is missing. Elsbeth holds her wedding

ring and the clasp of her blouse is formed with the initials NT,

presumably a gift from her husband. The initials WW worked into her blouse

and the mysterious letters MHIMNSK on the band over her voluminous

headscarf have so far defied interpretation. Just visible on her shoulders

is a gold necklace, evidence of her social standing. Above the parapet on

the left of the panel is a landscape, with a wood-fringed lake leading to

distant mountains, set beneath a stormy sky.

Durer also painted matching portraits of the brother of Niclas, Hans Tucher and his wife Felicitas (nie Rieter). In this diptych, it is the husband who holds a ring and his wife a flower.

Portrait of Oswolt Krel (1499)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Oswolt Krel for your computer or notebook. ‣

This portrait comes from the collection of the Princes

Oettingen-Wallerstein, who had acquired it in 1812; if has been in its

present location since 1928. It is presumed that Oswolt Krell, a merchant

for the Ravensburg House in Nuremberg from 1495 to 1503, had asked the

artist for a true portrait of representation. Its notable size, similar to

that adopted by Durer for the portrait of his father two years earlier,

and its setting, a half-length, suggests this. In this way, it differs from

the Tucher portraits, which were intended for private use.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Oswolt Krel for your computer or notebook. ‣

This portrait comes from the collection of the Princes

Oettingen-Wallerstein, who had acquired it in 1812; if has been in its

present location since 1928. It is presumed that Oswolt Krell, a merchant

for the Ravensburg House in Nuremberg from 1495 to 1503, had asked the

artist for a true portrait of representation. Its notable size, similar to

that adopted by Durer for the portrait of his father two years earlier,

and its setting, a half-length, suggests this. In this way, it differs from

the Tucher portraits, which were intended for private use.

The background, as in the Tucher portraits (Schlossmuseum, Weimar), is divided between the curtain and landscape passage, unlike those, however, it is divided rather unevenly. The bright red curtain is wide and occupies most of the space on the right; the landscape, on the left, is reduced to a foreshortening that shows a small part of a river that meanders toward the back, behind a group of tall trees. The windowsill that separated the subject from the landscape in the Tucher paintings is absent. The figure represented, set with obvious grandiosity, is found in front of the curtain, highlighted by intense colour.

The large fur-lined cloak is casually placed on the right shoulder only, to show, on the left side, the rich black garment with the puffed sleeve. To the disorderly folds of the cloak correspond the parallel horizontal folds of the sleeve and the vertical ones of the garment. The three-quarter position allows the painter to bring out the quality of the attire: the fur, silk shirt, and gold chain. The careful, fastidious representation of these meaningful details creates a powerful foundation for the setting of the head: vigorous, strong features, the pronounced nose and the strong-willed mouth, the furrowed eyebrows, as if from a sudden start or fright that makes him direct his gaze off to the side behind him. Everything works to make his face threateningly severe, which even the soft, light brown hair framing him does not attenuate. To the energetic expression of the face corresponds the nervous look of his left hand clutching his cloak and that of the contraction of the knotted fingers of the right hand that leans on an invisible window sill.

Colour, form, and proportion heighten the expression of supreme resolution, an expression that is the result of a serious psychological study that Durer conducted on the merchant, who was the same age as the artist and who was later to become the mayor of Lindau, his native city.

The two side panels that represent two "sylvan men" are wings to the portrait. They bear the heraldic shields of the subject and his wife, Agathe von Esendorf. They originally let the portrait be closed from the retro; one could imagine, then, that despite the large dimensions, the painting was to be conserved closed. The present frame has been made recently.

Portrait of St. Sebastian with an Arrow (1499)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of St. Sebastian with an Arrow for your computer or notebook. ‣

This primitive portrait has been partially repainted and transformed

into a Saint Sebastian with a large halo. Originally, the man wore a beret

and held a broken arrow in his left hand, which rests on the window sill,

as you can still see today. In the whole painting, only the landscape

passage with the lake and the castle in front of the mountains have

remained in its original state. The arrow is a fairly rare attribute for a

portrait, although, in this case, it could become credible if Sebastian

Imhoff were the person portrayed, as Thode had previously proposed when

the painting was first published in 1893. Sebastian Imhoff was elected to

the position of consul of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi in Venice in 1493.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of St. Sebastian with an Arrow for your computer or notebook. ‣

This primitive portrait has been partially repainted and transformed

into a Saint Sebastian with a large halo. Originally, the man wore a beret

and held a broken arrow in his left hand, which rests on the window sill,

as you can still see today. In the whole painting, only the landscape

passage with the lake and the castle in front of the mountains have

remained in its original state. The arrow is a fairly rare attribute for a

portrait, although, in this case, it could become credible if Sebastian

Imhoff were the person portrayed, as Thode had previously proposed when

the painting was first published in 1893. Sebastian Imhoff was elected to

the position of consul of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi in Venice in 1493.

The painting shows many Durerian portrait characteristics of this era, such as the landscape beyond the window and the resting of the hands in the window sill; the minimum of space between the window sill and the back wall; and the curtain that partially covers it.

Self-Portrait in a Fur-Collared Robe (1500)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Self-Portrait in a Fur-Collared Robe for your computer or notebook. ‣

The last of Durer's three magnificent self-portraits was painted early

in 1500, before his 29th birthday on 21 May. The picture is proudly

inscribed: 'Thus I, Albrecht Durer from Nuremburg, painted myself with

indelible colours at the age of 28 years.' It is a sombre image, painted

primarily in browns, set against a plain dark background.

a high-quality picture of

Self-Portrait in a Fur-Collared Robe for your computer or notebook. ‣

The last of Durer's three magnificent self-portraits was painted early

in 1500, before his 29th birthday on 21 May. The picture is proudly

inscribed: 'Thus I, Albrecht Durer from Nuremburg, painted myself with

indelible colours at the age of 28 years.' It is a sombre image, painted

primarily in browns, set against a plain dark background.

The face is striking for its resemblance to the head of Christ. In late medieval art, Jesus was traditionally presented in this manner, looking straight ahead in a symmetrical pose. Christ's brown hair in these images is parted towards the middle and falls over the shoulders. For the first and last time in Western art history, an artist was to portray himself in a Christ-like scheme. Given his idealized appearance as the underdrawing shows, his nose was originally irregular in shape - Durer is approaching us in "imitatio Christi", in imitation of Christ. He has a short beard and moustache. Durer has even painted himself with brown hair, although the other self-portraits show that it was actually reddish-blond. Durer deliberately set out to create a Christ-like image, with his hand raised to his chest almost in a pose of blessing. But this was no gesture of arrogance or blasphemy. It was a statement of faith: Christ was the son of God and God had created Man. For Durer, the painting was an acknowledgment that artistic skills were a God-given talent.

However, Durer has subtly departed from the traditional image of Christ in his self-portrait. Despite initial appearances, the picture is not quite symmetrical. The head lies just off the centre of the panel to the right and the parting of the hair is not exactly in the middle, with the strands of hair falling a little differently on the two sides. The eyes stare slightly towards the left of the panel. Durer also wears contemporary clothing, a fashionable fur-lined mantle. The result is a highly personal image, one whose 'indelible colours' still influence the way we imagine Durer looked in his later years.

The deceptive illusionism in which the picture is painted is also, however, a reference to the classical artistic legend about Apelles, with whom he had been compared by contemporary humanists.

Portrait of Young Man (1500)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Young Man for your computer or notebook. ‣

Durer's paintings include altarpieces, religious pictures and some

outstanding portraits. Although he began by working in the German late

Gothic tradition, Durer was to introduce the Renaissance to Germany with

his pure compositions in which the sure touch of the draughtsman is always

evident. With his workshop and followers he marked out the lines of

development of the new style for later years.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Young Man for your computer or notebook. ‣

Durer's paintings include altarpieces, religious pictures and some

outstanding portraits. Although he began by working in the German late

Gothic tradition, Durer was to introduce the Renaissance to Germany with

his pure compositions in which the sure touch of the draughtsman is always

evident. With his workshop and followers he marked out the lines of

development of the new style for later years.

This small picture - a portrait of a youth, painted in brilliant, warm colours - is sometimes ascribed to Durer's pupils (Hans Suss von Kulmbach or Hans Baldung Grien). Some scholars believe to recognize in the sitter Durer's brother Andreas; however the smooth features and simple attire hardly provide enough clues for identifying the sitter. However, a silverpoint drawing by Durer in the Albertina Collection in Vienna shows the same model in a similar pose, clearly indicated in the inscription as Endres Durer, the painter's younger brother.

Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman (1505)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman for your computer or notebook. ‣

The portrait is one of the first works of the artist during his second

sojourn in Venice. It was painted in the autumn or in the winter of 1505.

From the portraits, an extraordinary charm emanates, which cannot be

merely attributable to the shades of brown and gold of the hairdo and

clothing, which are set apart from the uniform black background. It is

really the beauty of the portrait that fascinates in its entirety and in

its variety of details. It is the slight wave of the hair on the clear,

high forehead that imperceivably becomes curls caressing the girl's

cheeks. It is the dreamy gaze that shows, under the slightly lowered

eyelids, the radiant, black eyes. It highlights the play of light on the

forehead and on the cheeks. It is the candour of this face, of the neck

and chest, emphasized by a neckline of a contrasting colour, that evoke the

image of the ideal purity of a girl. With great ability, the artist

includes in this image a long and pronounced nose and large, sensual lips,

immersing the whole figure in a light that reveals the important influence

of the Venetian school, and, in particular, that of Giovanni Bellini.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of a Young Venetian Woman for your computer or notebook. ‣

The portrait is one of the first works of the artist during his second

sojourn in Venice. It was painted in the autumn or in the winter of 1505.

From the portraits, an extraordinary charm emanates, which cannot be

merely attributable to the shades of brown and gold of the hairdo and

clothing, which are set apart from the uniform black background. It is

really the beauty of the portrait that fascinates in its entirety and in

its variety of details. It is the slight wave of the hair on the clear,

high forehead that imperceivably becomes curls caressing the girl's

cheeks. It is the dreamy gaze that shows, under the slightly lowered

eyelids, the radiant, black eyes. It highlights the play of light on the

forehead and on the cheeks. It is the candour of this face, of the neck

and chest, emphasized by a neckline of a contrasting colour, that evoke the

image of the ideal purity of a girl. With great ability, the artist

includes in this image a long and pronounced nose and large, sensual lips,

immersing the whole figure in a light that reveals the important influence

of the Venetian school, and, in particular, that of Giovanni Bellini.

With reference to some of the details, it has been repeatedly made known that the portrait is unfinished. It is probable that Durer deliberately did not give the same intensity to the left ribbon as to the right: on the one hand, so as to not overwhelm the charm of the dark eyes; on the other, so as to support the subtle chromatic effect of the bodice that, from the design of the gold ribbons, contributes to the overall charm of the painting.

This charm is also shown in the movement in the double rows of pearls, interrupted by the darker shapes of doubled cones, making the pendant curve slightly from the neck.

Among Durer's works, there is not a more beautiful portrait of a woman. Indeed, it has led one to think that there was a rather intimate relationship between the artist and the model. Some see the woman as a courtesan, others define her as an instinctive, languorous, and melting beauty.

Portrait of Burkard von Speyer (1506)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Burkard von Speyer for your computer or notebook. ‣

This striking portrait, painted in Venice, shows a thoughtful young

man, richly dressed and dramatically set against a black background. His

thick ginger hair, partly hidden by his dark hat, frames his face. The

small part of his red shirt showing adds a dramatic touch of colour.

Charles I acquired this work for the Royal Collection.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Burkard von Speyer for your computer or notebook. ‣

This striking portrait, painted in Venice, shows a thoughtful young

man, richly dressed and dramatically set against a black background. His

thick ginger hair, partly hidden by his dark hat, frames his face. The

small part of his red shirt showing adds a dramatic touch of colour.

Charles I acquired this work for the Royal Collection.

The sitter was identified as Burkard von Speyer after it was realized that he looks just like the man in a miniature in Weimar by an unknown artist, also dated 1506 and inscribed with his name. Nothing more is known about him, although presumably he originally came from Speyer, a town on the Rhine near Heidelberg. Burkard von Speyer also appears in The Altarpiece of the Rose Garlands. Wearing the same clothing, he is on the left side of the picture, just to the right of the first kneeling cardinal.

Portrait of a Venetian Woman (1507)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of a Venetian Woman for your computer or notebook. ‣

The painting is poorly conserved. Almost all the final layers of colour

are missing. The eyes have been restored. Because of the absence of the

topmost layer of colour, the painting has acquired a soft chromatic

shading. Even if we know that Durer executed it during his second sojourn

in Italy, probably in the autumn of 1506 after the Feast of the Rose

Garlands, workmanship seems particularly "Venetian." The refinement of the

artist is clearly absent in the sketching of the hair. Some object is

discernible in the curl hanging to the left.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of a Venetian Woman for your computer or notebook. ‣

The painting is poorly conserved. Almost all the final layers of colour

are missing. The eyes have been restored. Because of the absence of the

topmost layer of colour, the painting has acquired a soft chromatic

shading. Even if we know that Durer executed it during his second sojourn

in Italy, probably in the autumn of 1506 after the Feast of the Rose

Garlands, workmanship seems particularly "Venetian." The refinement of the

artist is clearly absent in the sketching of the hair. Some object is

discernible in the curl hanging to the left.

Only a few traces of the hairnet have been preserved, and the sky blue of the background, which is inexplicably divided into two sections, is probably no longer its original shade. In its original state, however, this half-bust must have been in the Venetian style, because of her full, soft shapes, delicately modeled with a measured use of light. We must count this painting among the most beautiful works Durer produced during his second sojourn in Venice.

The various attempts to identify the model - for example, as Agnes Durer, because of the letters AD on the trimming of the clothes or the woman with her head turned in the middle right of the Feast of the Rose Garlands - have not held up to criticism. The letters are probably the initials of a motto.

Portrait of a Young Girl (1507)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of a Young Girl for your computer or notebook. ‣

This small painting was in the collection of the Imhoff family of

Nuremberg, and cited in their inventory from 1573-74 until 1628. In 1633,

it was handed over, with the title Portrait of a Young Girl, with other

works by Durer, to Abraham Bloemart, an artist and merchant from

Amsterdam. In 1899, the portrait reappears in London, and the firm P. and

D. Colnaghi donated it to the Berlin art gallery.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of a Young Girl for your computer or notebook. ‣

This small painting was in the collection of the Imhoff family of

Nuremberg, and cited in their inventory from 1573-74 until 1628. In 1633,

it was handed over, with the title Portrait of a Young Girl, with other

works by Durer, to Abraham Bloemart, an artist and merchant from

Amsterdam. In 1899, the portrait reappears in London, and the firm P. and

D. Colnaghi donated it to the Berlin art gallery.

The delicate girl is portrayed with soft, curly blond hair, slightly dreamy her eyes, one somewhat lower than the other, a gentle, melancholic gaze; and well-defined, slightly parted lips. The red beret, worn sideways, with a little slit to the side, with a long red ruby and black pearl pendant, gives her a slightly cheeky air.

The square green border of the red bodice sets off the upper part of her body. All these details put together have led to various interpretations. In addition to the fact that the "girl," when sold by the Imhoffs, was transformed into a "boy," Panofsky (1955) attributes an androgynous nature to her that could reveal the possible homosexual tendencies of the artist. A teasing letter of 1507 from the canonical Lorenz Behaim of Bamberg and the fact that the portrait does not seem to have been ordered would support this hypothesis. It has also been debated whether the painting was executed in Venice or after Durer's return to Nuremberg. Considering the clothing to be typically German, there is no doubt as to its provenance.

Portrait of a Young Man (1506)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of a Young Man for your computer or notebook. ‣

This painting probably came from the collection of Rudolph II. Durer

returned to Nuremberg in the spring of 1507, after his second sojourn in

Venice. Opinions differ as to the whereabouts of the painting of this

portrait, which demonstrates, on the one hand, all the pictorial

characteristics of the Venetian tradition (following in the steps of

Giovanni Bellini, or Vicenzo Catena), and shows the depiction of a youth

wearing a typically Venetian beret, which would mean it was Venice; on the

other hand, the type of wood used for the panel, lindenwood, would have

its execution in Nuremberg, upon his return. It should be recalled that

Durer only used panels of poplar while in Venice, or, rarely, elm. The

alternative, regarding the setting and brightness of the portrait being

typically Venetian, in fact, is purely speculative.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of a Young Man for your computer or notebook. ‣

This painting probably came from the collection of Rudolph II. Durer

returned to Nuremberg in the spring of 1507, after his second sojourn in

Venice. Opinions differ as to the whereabouts of the painting of this

portrait, which demonstrates, on the one hand, all the pictorial

characteristics of the Venetian tradition (following in the steps of

Giovanni Bellini, or Vicenzo Catena), and shows the depiction of a youth

wearing a typically Venetian beret, which would mean it was Venice; on the

other hand, the type of wood used for the panel, lindenwood, would have

its execution in Nuremberg, upon his return. It should be recalled that

Durer only used panels of poplar while in Venice, or, rarely, elm. The

alternative, regarding the setting and brightness of the portrait being

typically Venetian, in fact, is purely speculative.

The portrait almost aggressively approaches the spectator. It is dominated by a light, slightly reddish face, an intense, far-off gaze, a short and robust nose, a wide mouth, and turgid lips surmounted by a hint of downy hair. Even the beard under the chin is delicate and contrasts with the almost frizzy hair, painted with an extremely thin brush. Despite the fact that the painting is not completely preserved in this area, one can still appreciate the extraordinary skill of execution. One appreciates above all the difference between the stroke used for the hair and the one, just as skillful though different, adopted for the hairs of the fur collar, giving a showy trim to the coat. His talent drew praise from the Venetians and particular admiration from Giovanni Bellini. The snow-white of the shirt represents the third note of colour of the painting, next to the delicate pink of the flesh and to the black, found in the elegantly worn beret and in the clothing, silhouetted against the similarly black background.

He employs what he learned from Venetian painting and his special talent for painting, with very fine strokes for hair and fur - a talent that markedly distinguishes him from his Venetian colleagues. Durer thus manages to vivify even a face like this one, that except for the mouth, has rigid and immobile features, and for that, on the whole, is not very expressive.

On the reverse side, without a preparatory drawing and with light brush strokes, an ugly old woman is painted, who winks rather obscenely. She reveals her nude breast and holds a bag of coins. With the original frame lost, it is unfortunately impossible to know if this small painting was to be part of a diptych, as some have put forward.

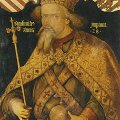

Emperor Charlemagne (1512)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Emperor Charlemagne for your computer or notebook. ‣

Durer's only commission for panel paintings from Nuremberg's city

council was for a pair of portraits of the Emperors Charlemagne and

Sigismund. These were ordered for the Treasure Chamber in the Schopper

House, where the imperial regalia were kept the night before they went on

ceremonial display on the Friday after Easter. For the rest of the year

the regalia were housed in the Church of the Hospital of the Holy Ghost.

Durer was probably commissioned for the portraits in 1510 and received his

final payment three years later. His panels are believed to have been

ordered to replace two earlier works, now lost, which had been painted

soon after the regalia were brought to Nuremberg in 1424.

a high-quality picture of

Emperor Charlemagne for your computer or notebook. ‣

Durer's only commission for panel paintings from Nuremberg's city

council was for a pair of portraits of the Emperors Charlemagne and

Sigismund. These were ordered for the Treasure Chamber in the Schopper

House, where the imperial regalia were kept the night before they went on

ceremonial display on the Friday after Easter. For the rest of the year

the regalia were housed in the Church of the Hospital of the Holy Ghost.

Durer was probably commissioned for the portraits in 1510 and received his

final payment three years later. His panels are believed to have been

ordered to replace two earlier works, now lost, which had been painted

soon after the regalia were brought to Nuremberg in 1424.

The half length pictures are larger than life. No likenesses are known of Charlemagne, who ruled from 800-14, and Durer therefore invented his portrait, presenting him frontally in an imposing posture. His interpretation of Charlemagne's appearance was to influence depictions of the Emperor until well into the nineteenth century. For Sigismund, who ruled from 1410-37, Durer must have had access to a portrait done during his reign.

The two paintings include the appropriate coats of arms, the German eagle and French fleur-de-lis for Charlemagne and the arms of the five territories ruled by Sigismund, the German Empire, Bohemia, Old and New Hungary and Luxembourg. Inscriptions name the two men and state the number of years they ruled, 14 years for Charlemagne and 28 for Sigismund. Around the four sides of the panels are explanatory texts on the frames. The first records: 'Charlemagne reigned for 14 years. He was the son of the Frankish King Pippin, and Roman Emperor. He made the Roman Empire subject to German rule. His crown and garments are put on public display annually in Nuremberg, together with other relics.' On the second panel is the text: 'Emperor Sigismund ruled for 28 years. He was always well-disposed to the city of Nuremberg, bestowing upon it many special signs of his favour. In the year 1424, he brought here from Prague the relics that are shown every year.'

The idealized portrait of Emperor Charlemagne was intended for the "Heiltumskammer" in the Schoppersche House by the marketplace, together with the portrait of Emperor Sigismund of Poland (also in Nuremberg). This was where the coronation insignia and relics were kept, which were put on display once a year at the so-called "Heiltumsweisungen." The physiognomy of Charlemagne, shown in the magnificent original coronation robes, is reminiscent of depictions of God the Father. The crown, sword and imperial orb were prepared by Durer in sketches. The German imperial coat of arms and French coat of arms with the fleur-de-lis are emblazoned at the top.

Emperor Sigismund (1512)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Emperor Sigismund for your computer or notebook. ‣

Although the two panels were originally designed as a diptych, they

were ultimately displayed separately. Other texts on the reverse of the

panels suggest that the painted side was normally hung facing the wall,

with the portraits only being shown on special occasions, presumably for

the annual display of the regalia. The two panels were hung on either side

of the shrine in which the relics were housed.

a high-quality picture of

Emperor Sigismund for your computer or notebook. ‣

Although the two panels were originally designed as a diptych, they

were ultimately displayed separately. Other texts on the reverse of the

panels suggest that the painted side was normally hung facing the wall,

with the portraits only being shown on special occasions, presumably for

the annual display of the regalia. The two panels were hung on either side

of the shrine in which the relics were housed.

Durer prepared studies of the individual pieces of the regalia and reproduced them with great accuracy. Charlemagne wears the imperial crown and brandishes his sword and orb. Sigismund has a Gothic crown and holds a sceptre and orb. The annual display of the imperial regalia ended in 1525 and Durer's panels were then moved to the city hall. Since 1880 they have been on loan to the Germanisches Museum in Nuremberg. As for the regalia, the Habsburgs later took them to Vienna where they remained in the imperial treasury, except for a brief period when they were seized by the Nazis and returned to Nuremberg.

Durer had originally planned the two imperial portraits of Charlemagne (also in Nuremberg) and Sigismund to be a foldable diptych. In accordance with the prescriptions of the Nuremberg town council, who had commissioned the works, the two portraits were supposed to be based on the paintings which had previously decorated the "Heiltumskammer" in the Schoppersche House by the marketplace, where every year the state jewels were kept for a short time. Emperor Sigismund is turned towards Charlemagne. The portrait, which is rather wooden in appearance when compared to other portraits by Durer, presumably was based on a miniature copy in a portrait book by Hieronimus Beck of Leopoldsdorf, which is in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. The coats of arms of the German Empire, Bohemia, old Hungary, new Hungary and Luxembourg appear at the top of the painting.

Portrait of Michael Wolgemut (1516)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Michael Wolgemut for your computer or notebook. ‣

After he had achieved great fame, Durer depicted the master who had

taught him to paint. On it he inscribed: 'This portrait was done by

Albrecht Durer of his teacher, Michael Wolgemut, in 1516', to which he

later added, 'and he was 82 years old, and he lived until 1519, when he

departed this life on St Andrew's Day morning before sunrise.' It is

unclear from the inscription whether Wolgemut was 82 when he died or when

the portrait had been painted three years earlier.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Michael Wolgemut for your computer or notebook. ‣

After he had achieved great fame, Durer depicted the master who had

taught him to paint. On it he inscribed: 'This portrait was done by

Albrecht Durer of his teacher, Michael Wolgemut, in 1516', to which he

later added, 'and he was 82 years old, and he lived until 1519, when he

departed this life on St Andrew's Day morning before sunrise.' It is

unclear from the inscription whether Wolgemut was 82 when he died or when

the portrait had been painted three years earlier.

Michael Wolgemut (1434/7-1519) had one of the largest artist's workshops in Germany. Durer had served his apprenticeship there from 1486 until 1489 and Wolgemut must have been proud to have witnessed his former pupil's rapid success. In Durer's portrait, everything is focused on the head, set against a neutral green background. The old man's features are not disguised, from his sunken eyes and gaunt cheeks to the loose skin around his neck. Wolgemut wears a fur-lined coat and a simple hat or scarf, perhaps the headgear he would have worn in his workshop to keep off the dust. His eyes are still alert and he has a thoughtful expression. Durer does not depict a pitiable man, but marvels at his indomitable spirit.

Portrait of a Cleric (1516)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of a Cleric for your computer or notebook. ‣

The painting was considered in Nuremberg (1778) to be of Johann Dorsch,

an Augustinian friar who had converted quite early on to Lutheranism. This

identification, however, was challenged by various critics, since Dorsch

became the parish priest of Saint John's in Nuremberg in 1528. Some have

hypothesized that it was a portrait by Huldrych Zwingli, the great Swiss

reformer; but only side profile portraits of him exist, which do not give

rise to a fair comparison or to a reliable attribution. Most critics would

opt for the former identification, also because, according to more recent

studies, the meeting between Zwingli and Durer could not have occurred

before 1519, on the occasion of a mission in Zurich in which he

participated with his friend Pirckheimer and Martin Tucher.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of a Cleric for your computer or notebook. ‣

The painting was considered in Nuremberg (1778) to be of Johann Dorsch,

an Augustinian friar who had converted quite early on to Lutheranism. This

identification, however, was challenged by various critics, since Dorsch

became the parish priest of Saint John's in Nuremberg in 1528. Some have

hypothesized that it was a portrait by Huldrych Zwingli, the great Swiss

reformer; but only side profile portraits of him exist, which do not give

rise to a fair comparison or to a reliable attribution. Most critics would

opt for the former identification, also because, according to more recent

studies, the meeting between Zwingli and Durer could not have occurred

before 1519, on the occasion of a mission in Zurich in which he

participated with his friend Pirckheimer and Martin Tucher.

As in the portrait of Wolgemut (Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg), Durer succeeds in effectively expressing the vigorous personality of the subject, modeling the head with a slight rotation leftward, toward the light, and framing it with a severe black attire against a green background. The fine brush strokes, especially for the hair and eyelashes, are well preserved.

Portrait of Emperor Maximilian I (1519)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Emperor Maximilian I for your computer or notebook. ‣

Maximilian I of Austria (1459-1519) became head of the Habsburgs in

1493 and was elected Holy Roman Emperor in 1508. He was a learned ruler

with a strong interest in the arts. Durer first met him during a visit to

Nuremberg in 1512 and was commissioned to work on the gigantic woodcuts of

The Triumphal Arch and The Triumphal Procession, as well as decorations

for Maximilian's prayer book. In 1515 he was awarded an annual payment of

100 florins by the Emperor.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Emperor Maximilian I for your computer or notebook. ‣

Maximilian I of Austria (1459-1519) became head of the Habsburgs in

1493 and was elected Holy Roman Emperor in 1508. He was a learned ruler

with a strong interest in the arts. Durer first met him during a visit to

Nuremberg in 1512 and was commissioned to work on the gigantic woodcuts of

The Triumphal Arch and The Triumphal Procession, as well as decorations

for Maximilian's prayer book. In 1515 he was awarded an annual payment of

100 florins by the Emperor.

On 28 June 1518 Durer had sketched Maximilian during the Imperial Diet at Augsburg. He inscribed the drawing: 'This is Emperor Maximilian, whom I, Albrecht Durer, portrayed up in his small chamber in the tower at Augsburg on the Monday after the feast day of John the Baptist in the year 1518.' In the relatively informal sketch Durer captured a hint of the fatigued resignation of the 59 year-old ruler.

Maxmilian I died on 12 January 1519 and Durer then used his drawing as the basis for a woodcut and two painted portraits, one in tempera (Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg) and this one in oil. These finished works are formal portraits and lack some of the human character which comes out in the original sketch. In the oil portrait, the Emperor is dressed in an elegant fur, which Durer has painted with great care. Instead of an orb, the Emperor holds a broken pomegranate, a symbol of the Resurrection and Maximilian's personal emblem. At the top of the picture is the Habsburg coat of arms with the double-headed eagle and a lengthy inscription on Maximilian's achievements. The Emperor looks aloof and withdrawn, an expression of his dignity.

Jakob Fugger, the Wealthy (1520)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Jakob Fugger, the Wealthy for your computer or notebook. ‣

The presence of this portrait is documented, in the eighteenth century,

in the gallery of the elector of Bavaria. Because of successive

restorations, the top layer of colour is missing.

a high-quality picture of

Jakob Fugger, the Wealthy for your computer or notebook. ‣

The presence of this portrait is documented, in the eighteenth century,

in the gallery of the elector of Bavaria. Because of successive

restorations, the top layer of colour is missing.

During the Diet of Augsburg, in 1518, Durer portrayed Jakob Fugger in a charcoal drawing. The final painting, on canvas, differs from the drawing in the wealthier clothing of the subject, and, above all, in the framing: a half-bust in the drawing, a half-length in the painting.

Jakob Fugger of Augsburg (1459-1525), the wealthiest merchant of his day, learned the art of commerce in Venice. He possessed a network of business agencies throughout Europe. His was the most important banking institution in Europe, and he had the monopoly of silver and copper mines. He obtained the right to mint the coins of the Vatican from Julius II, Leo X, and Adrian VI, and he had an important role in the system of tax collection and payment of indulgences from the Vatican coffers. He heavily financed the political and military undertakings of Maximilian I and Charles V: just for the election of the latter, he contributed 300,000 florins. In 1508, Maximilian I conferred him a noble title, and Leo X nominated him Count Palatine of the Lateran. In 1519, he established in Augsburg the "Fuggerei," a small city within the city, consisting of 106 small houses intended for the most needy citizens.

The outer edges of his garments and fur coat, crossing and overlapping, create an ascendant pyramid effect, which solidly sets off the portrait. At the same time, his garments sharply contrast with his face, hard and severe, atop a bull neck. Only the clear complexion of the flesh, painted with extremely fine brush strokes, which is detached from a delicate blue background, attenuates his dynamism and severity. The position of the head denotes firmness and self-assurance, and the eyes look away, possibly to indicate a farsightedness. The wide forehead, lined with a simply-fashioned gold beret, and the thin, pressed lips, give him the look of a man who - at least according to Durer's interpretation - has a strong personality and no need of decoration to assert himself.

This impressive characterization, if somewhat idealized, along with the one of Durer's father of 1497 (National Gallery, London), is probably one of the most significant of portraiture in that era in Europe.

Portrait of Bernhard von Reesen (1521)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Bernhard von Reesen for your computer or notebook. ‣

The man in the portrait holds a message on which the first few letters

of his name can be read 'Bernh', the rest being hidden by the

fingers of his left hand. This is almost certainly the painting to which

Durer refers in his Antwerp diary in late March 1521, recording that he

had 'made a portrait of Bernhart von Resten in oils' for which he had been

paid eight florins. Durer's reference is probably to Bernhard von Reesen

(1491-1521), a Danzig merchant whose family had important business links

with Antwerp. His name suggests that his family originated from Rees, a

town on the Lower Rhine 100 miles east of Antwerp.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Bernhard von Reesen for your computer or notebook. ‣

The man in the portrait holds a message on which the first few letters

of his name can be read 'Bernh', the rest being hidden by the

fingers of his left hand. This is almost certainly the painting to which

Durer refers in his Antwerp diary in late March 1521, recording that he

had 'made a portrait of Bernhart von Resten in oils' for which he had been

paid eight florins. Durer's reference is probably to Bernhard von Reesen

(1491-1521), a Danzig merchant whose family had important business links

with Antwerp. His name suggests that his family originated from Rees, a

town on the Lower Rhine 100 miles east of Antwerp.

Durer's tight composition cuts off the two edges of Reesen's hat, emphasizing his brightly lit face. The dark clothing and hat also draw attention to his features - his pronounced cheekbones, forceful chin and youthful expression. His eyes stare out into the distance. Reesen, who was 30 when he was painted, died from the plague just a few months later in October 1521.

The well-preserved state allows for a full appreciation, from a formal point of view and a pictorial one, the mastery of the painter. He gives the thirty-year-old subject an intense physical and spiritual charm. This work further demonstrates the extraordinary span of Durer's portraiture up until his final years.

Portrait of a Man with Baret and Scroll (1521)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of a Man with Baret and Scroll for your computer or notebook. ‣

There is an inscription near his head, monogrammed and dated 152?.

The last digit of the date is not clearly legible (1 or 4), but the fact

that the panel is oak indicates that the painting must have been carried

out during Durer's trip to the Netherlands. The hypotheses regarding the

name of the subject are various. The most frequent are: the one of Lorenz

Sterck, an administrator and financial curator of the Brabant and of

Antwerp, and that of Jobst Plankfelt, Durer's innkeeper in Antwerp. These

names are frequently suggested since Durer writes in his diary that he had

done oil portraits of them.

a high-quality picture of

Portrait of a Man with Baret and Scroll for your computer or notebook. ‣

There is an inscription near his head, monogrammed and dated 152?.

The last digit of the date is not clearly legible (1 or 4), but the fact

that the panel is oak indicates that the painting must have been carried

out during Durer's trip to the Netherlands. The hypotheses regarding the

name of the subject are various. The most frequent are: the one of Lorenz

Sterck, an administrator and financial curator of the Brabant and of

Antwerp, and that of Jobst Plankfelt, Durer's innkeeper in Antwerp. These

names are frequently suggested since Durer writes in his diary that he had

done oil portraits of them.

It is difficult to imagine an innkeeper who made himself depicted with a scroll in his hand. Whereas it seems much more plausible that the imposing subject characterized by a severe and scrutinizing gaze - clad in a silk shirt, a cloak with a fur collar, and a large beret - corresponds to a tax collector. But whoever the subject is, the portrait is regardless one of the most beautiful and incisive that Durer ever created. He manages, with an image constrained by such a limited space, to communicate the impression of being in front of a personality of a supremely concentrated energy - and all that by using simple and pale colours, whose effect is unfortunately partly obfuscated by the heavy varnish covering the painting.

Portrait of Hieronymus Holzchuher (1526)

Get

Get  a high-quality picture of

Portrait of Hieronymus Holzchuher for your computer or notebook. ‣

Durer painted this portrait in Nuremberg in 1526, when the sitter was

57 years old. Hieronymus Holzschuher (1469-1529) came from an old Nuremberg

patrician family. In 1500 he was elected junior, and nine years later

senior burgomaster. In 1514 he ranked as one of the seven Elders of the

city government, and on his death in 1529 a commemorative medal bearing